One of my favorite conferences every year is Microconf , because it focuses on small software businesses, which is where my heart and soul is businesswise. I know a lot of folks can’t justify a trip out to Vegas (though you should really come in 2014 if you possibly can — 2013 is only a few days from me posting this and already quite sold out), so I always ask Rob and Mike (the organizers) for a copy of my video so I can produce a transcript and put it online. My 2012 talk focuses on building systems to achieve marketing objectives at a software company. I’ve been successful at doing things at a variety of scales, from my own one-man software business to consulting clients with 8 figures a year of revenue. A lot of the tactics covered are wildly actionable if you run a SaaS business.

[Patrick notes: As always, I include inline notes in my transcripts, called out like so. If you’d like to see my 2011 talk, see here. It focused on how to run a software business in 5 hours a week, including scalable marketing strategies like SEO/AdWords/etc.

Video & Slides (Transcript follows)

Transcript: Marketing, For People Who Would Rather Be Building Stuff

Patrick McKenzie: Hideho everybody, my name is Patrick McKenzie, perhaps better known as “Patio11″ on the Internet.

I sometimes get asked what I do, and I’m kind of confused at it myself. I was going to Town Hall recently to file my taxes, and I was across the street from Town Hall, the light was preventing me from getting across the street. By the way, I live in Japan. A guy comes up to me on a cycle, stops right next to me and says, “Psst! 日雇い労働ですか?” [Patrick notes: I corrected the Japanese here with reference to a dictionary, but don’t remember this as being his phrasing.] My brain started to flip through all the possible things that could be, and a high probability for those characters, hiyatoi roudou is day labor, “Are you a day laborer?”

I was like, “Wow, there’s only one way I can answer that. ‘Yeah, but my rates are probably a little high for you.'” [Patrick notes: Unstated background knowledge here: I live in Ogaki, where roughly 90% of foreigners — who are rather scarce — are blue collar Brazilian Japanese who largely work in electronics/car parts factories. Unemployment among these folks has been rather high for the last couple of years, so if you were doing things purely on a statistical basis, “Day laborer” is a much less insane guess for a foreigner standing outside city hall than “Owner of a software company.”]

[laughter]

If you were here last year, you heard the grand arc of my transition from really overworked Japanese salary man to totally‑not‑working‑all‑that‑much Bingo Card empire guy. It’s really not all that great shakes compared to some of the things that people have done up here, but it’s the little website that could. It has over 200,000 users and 6,056 paying customers. [Patrick notes: Current counts as of posting are ~300,000 and 8,249. The last twelve months have been pretty good.] I’m pretty happy with where it got me to, and just for a little update on this story for last year, if you weren’t here for last year, it’s on the blog somewhere.

I’m sure people will tweet out the link to that video if they’re very, very nice and kind to me. [Patrick notes: The Microconf 2011 writeup is here.] Just an update. The blue bars here are the 12 months before attending Microconf, and the red bars are the last 12 months, so after attending Microconf. Since my business is crazily seasonal, if the red bar is above the blue bar, I’m doing something right. As you can see, in the last six months, the red bar is routinely exceeding the blue bar, so I was doing something very right. The thing that I was doing was stopping working on Bingo Card Creator.

So my first actionable tip is, “If you have me in charge of your marketing,” like say Jason Cohen does, “you need to fire me, and your sales will go up by 50 percent.” We’re not going to talk too much about Bingo Card Creator today, we’re instead going to talk about systems. You heard earlier about building the flywheel, being a growth hacker. This is probably one of the most important things I’ve ever come across, but a job is a system that turns time into money, and a business is a system that turns systems into money.

I was once talking to a Japanese guy at a large automobile manufacturer in central Japan that you might know of, and I said, “T‑Corp is known in America as a company that makes cars, and Ford, or whatever, is a company that sells cars.” He patted me on the head like, “Oh, nice. Silly American. Ford might well be a company that sells cars, but T‑Corp is a company that builds organizations that builds cars.”

Why Engineers Get A Cheat Code For Starting Businesses

I thought that was a very profound distinction. All of us are in the business of building things that help us sell things that we build. I think we are ideally situated to this, because, as engineers, we build systems. You heard earlier about the term “growth hack,” which is just on the cusp of becoming a meme, by the way. You’re going to hear a lot about that over the next coming days, because there are huge platforms these days, everything from Pinterest to Twitter, to Google, to the App Store, that give you ready access to hundreds of millions of users, billions of users, many of whom have credit cards and will actually pay money for things. [Patrick notes: I’m stealing this from 500 Startups’ investment thesis, but I think it is equally applicable regardless of whether one is doing a high-growth startup or a one-man bootstrapped software company. Again, the most niche app you could think of, run by an unknown guy living in Central Japan, just added 100,000 users last year while in maintenance mode due to effective use of Google as a platform.]

As engineers, we have the capability of exploiting those platforms in a scalable manner. Some of the ways to do it I talked about last year, and I don’t want to give all old content, so if you want to hear about SEO, which is the main reason my sales went up for this year, just watch the thing from last year. [Patrick notes: Or you can read my copious writeups of it in the Greatest Hits section under SEO or Content Creation.] We’re going to talk about new stuff. Oh, totally stealing a slide from last year. In addition to Bingo Card Creator, there were three really big things going on, and I just want to give you updates on them.

The most important one, down in the bottom there. Last year I said something out of school, it wasn’t planned for the talk or anything, it just slipped out of my mouth. I said, “The most important thing in my life right now is I’ve recently met a beautiful young lady, Miss Ruriko Shimada over there, and she is going to be the future Mrs. McKenzie.” That was the first time that thought ever got verbalized, even in the deepest recesses of my mind, so luckily it was not simulcast or anything. That’s official now, it’s happening June 26. [Patrick notes: Ruriko’s only comment on the presentation was “The 23rd, dear. Be there.“]

[applause]

Thanks very much. I don’t have a picture of kids, for obvious reasons, but can I just make a note about this? Everyone has shown a picture of their children or significant other. At a less charitable conference, people might be, “Oh, that’s the boring stuff, skip that, get to the good stuff.” All those other pictures, that is the good stuff. There’s a word in Japanese called mono no aware (もののあわれ), meaning “an awareness of the impermanence of things.” All this conversion rates and equity grants and profits and all this… Vegas?

[laughter]

This will all be dust and memories. The important part of our lives is our families, our friends, that is what we will be known for. If you have a successful business, and your family isn’t feeling it, something is going terribly, terribly wrong. I can’t just stand up in here and say, “My fiancee is the nicest, smartest, most wonderful, beautiful woman in the world,” for the entire hour.

[laughter]

#include <platitudes.h>… wait, the word I wanted is not platitudes, it’s compliments, drats. I don’t speak the Engrish. Anyhow, updates on other things that are going on. I got a slide up from Fog Creek, which was one of my favorite clients I can publicly talk about, but I don’t really have much content in this presentation about running a high‑priced consulting business. Is that something you guys are interested in? Let’s have a show of hands.

I’m a marketing guy, so let me give you the quick elevator pitch, and if you want to hear about this, we can talk about it at the question‑and‑answer session. Is it interesting to you how I turned down $700,000 a year to do conversion optimization for big software companies? Just raise a show of hands. Would that be fun? Oh, OK. We might talk about that before questions. We’re going to talk a little about “Appointment Reminder” stuff that I learned the second time I tried to make a software business from the ground up, and how you can apply it to your businesses.

This is my new thing, which is, by the way, in almost direct competition to somebody who was in the first session of tear‑downs. You might compare and contrast to the way I do it and the way he does it. I actually went up to him afterwards and tried to teach him what I know about this, because people helping people is what this event is all about. We all get better, even if we’re competitors, sharing knowledge. Anyhow, it makes “Appointment Reminder”, phone calls, text messages and email messages to the clients of professional services businesses.

Don’t Make My Mistakes In Picking A Software Business

This is a wee bit more sophisticated than my bingo thingy. Why did I pick this problem? This is the slide in which I give bad advice. The way you should actually pick a problem, skip back to your notes from Amy Hoy’s presentation. That’s the way you should pick a problem. This is not the way you should pick a problem, but it’s true, so I’ll tell you it anyhow. You see this jacket that I wear in all of my presentations, because the color red looks good on me, and I love this company, Twilio?

Twilio came out with this product that let Web developers basically script up phone calls and SMS messages. I thought, “Ooh, that’s kind of awesome.” I like to view the market, “The market” in the sense of the broad, capital‑C Capitalism sense of the market, as a placid lake, which incorporates everything we know about the world right now. When new information gets added to that, it’s like dropping a rock in the lake. Ripples in the lake are change, and the larger the ripple is, the more change there is, the more possibility there is to get outsized profits over the course of the world right now.

Because we learned from microeconomics 101, the natural state of profits in the system is zero. The steady state. Twilio was dropping a big F‑ing rock into the software world, because you can finally interface with the plain old telephone system without having to understand what an Asterix server is, and if anyone here has ever tried to hack Asterix, I’m sorry for you. What could I do with a telephone that I couldn’t do before? I made a list of 400 ideas and just sat on it, because I was still at the day job at the time. Since I spend 16 hours a day in front of a computer screen, my shoulders ache like crazy, so I sometimes go to massage therapists.

This one day I went into a massage therapist, and asked, “Hey, can I get a shoulder massage, because I’m an engineer, my shoulder aches like crazy.” She said, “It’s going to be about two hours,” and I’m like, “Oh, well I’m gainfully unemployed, so that’s no problem. I’ll just take my iPad, browse Hacker News in the corner here for a little while, then we’ll get the massage when you can do it.”

15 minutes later, she comes back to me and said, “Hey, I know I told you it would take two hours, but it would be really, really helpful for me if I could massage your shoulders right now.” I said, “Sure, no problem, can I ask why?” She said, “I had this slot booked up with somebody else, but he didn’t come in, and now he’s 15 minutes late. If I don’t start massaging your shoulders now, that’s going to throw off the schedule for the rest of the day, and I’ll never get the revenue from these next 45 minutes back.”

I’m like, “That’s interesting. Why don’t you call him?” Notable and quotable line from her, she says, “I’m a massage therapist. If my hands are on a telephone, they’re not on someone’s back, and if my hands aren’t on someone’s back, I’m not making money,” and I thought, “That’s interesting.” I asked, “If I had a system that could call someone automatically before their appointment with you, would that be motivational to you?” and she said, “Yeah.” I went through my list of 400 things, and thought, “This is the first one I’ve had an actual customer need for.”

How did I know it would sell, though? That’s one person. I did two things. One thing I did was just whipped up the MVP, Minimum Viable Product, read Eric Ries’s book “The Lean Startup.” Everyone should read that book, it’s amazing. I whipped up the MVP, which is a website, you can get to it, I’ll show you the link later. You give in your phone number, and it calls you, just like you had an appointment, and says, “Hey, you’ve got an appointment. Click ‘One’ to confirm.”

If you confirm it shows right on the schedule here, “This person confirmed.” If you cancel, it says, “This person canceled.” We would email you right now so you can re‑book the slot and save the money. I just threw this up on the Internet, and waited. People signed up for my pre‑launch list, and said, “That is exactly what my problem is.” The other way I did, was I went home to Chicago, which is where my family is from, and took out $400 from an ATM, and walked around downtown Chicago and looked for salons and other massage therapists, that sort of thing.

I walked in and said, “Hey, do you take walk‑ins?” “Yeah.” “Are you free right now?” “Yeah.” “Are you the business owner?” “Yeah.” “OK, I’ve got a weird proposition for you,” and no, not that kind of weird.

[laughter]

“What’s the rate on a 30‑minute shoulder massage?” She would tell me. It’s almost always a she. I would say, “OK, I’m going to pay you the rate for a 30‑minute shoulder massage, but what I’m really interested in, I’m a small businessman, I live in Japan, I’m interested in the business of massage therapy. How about we just skip to that post‑massage cup of tea that you’re going to offer me,” I have learned this over the years. “Skip to the cup of tea, I’m going to pick your brains about how you run your business, and then I’ll go, no massage needed, and you get your money?” Almost everybody took me up on that, and nobody called the police. Yay.

[laughter]

I would ask questions, like, “What do you use for your appointment scheduling right now?” “Pen and paper version 1.0.” “How many people cancel?” “Lots.” “Do you not like when people cancel?” “Yes.” “Do you phone call people every day?” “Well, yeah, I kind of do, but I sometimes forget,” yadda yadda yadda.

Then the money question. “If I had something that I could show you right now that would call, would you pay for it?” “Yes.” “Would you pay $30 a month for it, because $30 a month is close to your rate for just saving one appointment?” “Yes.” “Can I get your email address right now? As soon as this is ready, I’m going to come back to you and say, ‘It’s ready. Let’s get that $30 a month,'” and I just collected those.

I actually didn’t end up selling any one of those people, but the need was clearly demonstrated to me there. I’ve got a better way for doing it these days, because as I mentioned, I am in the talking‑to‑people‑about‑wedding‑things, and I’m learning stuff about selling wedding dresses, because I am the unwitting victim of that. There’s this thing called the iPad, and every salesman at a wedding venue or a wedding dress shop, or whatever, in Japan, is using the iPad. I predict within five years, that every salesman in the entire world will consider that their key sales tool.

The reason is, when you have a sales discussion with someone with the iPad, you’re sitting next to them, standing next to them, hunched over the shoulder in a very intimate, psychologically‑reassuring way, while they drive the iPad and flip through. “Oh, that’s a lovely dress. Oh, that’s lovely, I really like that one.” “You like that one? I’ll show you more like that.” When they get confused, you can just take over for them, do the little slide‑y slide‑y thing, and it is a very, very persuasive technique.

If you don’t know whether a software will sell or not, go to WooThemes, or go to ThemeForest, pay $15 or $70, or whatever it is, mock up three screens from it, or even mock up two screens plus the final output. Put them in a photo gallery on your iPad, and take it directly to people in real life. Stand out and then listen over the shoulder, it’s like, “Do you really have a wedding dress problem? We got these.” If you’re solving a problem people actually have, they will say at this point, “Shut up and take my money.”

[laughter]

If someone says, “That’s kind of interesting, tell me when that exists,” you have not successfully identified a problem that people actually have. Fail to identify problems prior to spending six months of your life building the solution to those problems that no actual human being, aside from you, actually experiences in their life. You will have much better success that way. Brief interlude on pricing. This was brought up in a few things, and we treated it at a high level, so I thought I would dig into the nuts and bolts, considering many of you are in the software‑as‑a‑service business.

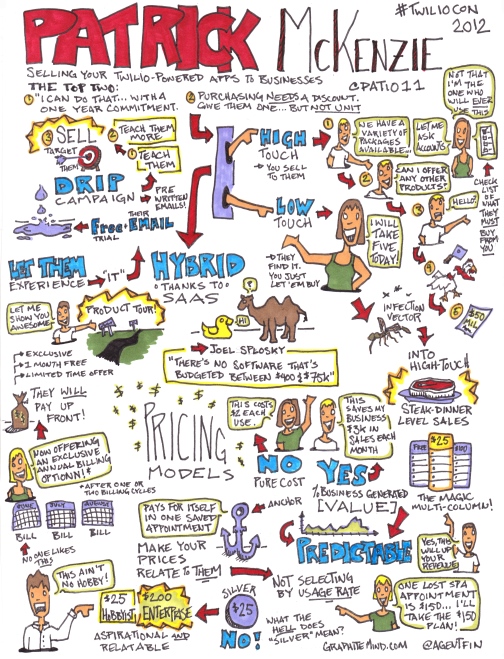

How To Read A SaaS Pricing Grid (And Why You Should Charge More)

I thought I’d read a pricing grid. This one’s from Wufoo. You have seen similar things all over the Internets. I can’t tell you about exact results I’ve gotten from customers, but I talk to a lot of people about this sort of things, so if we’re just kind of anonymizing, here’s how you read it. Find the largest dollar‑amount plan. That plan generates 33 percent to 50 percent of gross revenue. Why? Because it’s sold to people who are not spending their own money, they’re spending a corporate budget. Spending your own money hurts, but spending a corporate budget is kind of the happy thing for a lot of people.

[laughter]

Because, check this out, if you don’t spend your budget, it gets taken away from you. If you’re trying to protect your home position at a company, you want to spend as close to the top of that budget as possible, so help people out. They’re trying to protect their status and job security, by helping them spend their budgets. $200 a month is nothing to a company that has actual employees. The cheapest possible fully‑loaded cost for a college graduate is about $4,000 a month.

$200 a month is five percent of that, so if you’re only spending one or two hours of employee time a month, $200 is a total no‑brainer. So’s $250. Anyhow, the one that has the most users. Nobody likes to be a cheapskate, boom, it’s this one. The one that has the highest support costs. Wufoo has a free plan, I’ll guarantee you they get more annoying emails from people on the free plan than anything else put together, probably squared.

[laughter]

The worst customers, I call them pathological customers, are attracted to things that don’t have a lot of money. It’s amazing how many people have told me this. You raise prices, and you deal with less crazy people. At 99 cents, people have very unreasonable expectations. “What? This flashlight app didn’t do my taxes! One stars!”

[laughter]

When you’re charging people tens of thousands of dollars a month for an enterprise‑level service, they say, “Hey, our business really needs this feature.” “Oh, thanks for the email. I would really love to implement that feature, but we are kind of constrained on time right now. Can I get back to you in the indefinite future, if we get time to do that?” You’ll get a one‑line email back, “Sure, that sounds great.”

Would you rather deal with the no stress and get the tens of thousands of dollars, or “One stars!” for 99 cents? It’s almost self‑explanatory. By the way, I’ve sold a semi‑B2C product for most of my life. I really do love teachers, even when they’re kind of exasperating, and can’t tell the difference between the blue Googles and the green Googles, and don’t understand why they can’t get a CD of the Internet. It actually happened to me today.

[laughter]

In terms of, if I had known then what I know now, I would never go into B2C. Charge businesses, charge them a price appropriate to the value you’re providing. By the way, big surprise about software‑as‑a‑service companies, almost every one has enterprise pricing available. Some of them don’t put it on your things, but I guarantee you there’s a way to go up to Wufoo, go up to almost any software‑as‑a‑service company, and pay arbitrary amounts of money for their product. For example, if you have a $500,000 budget, and you talk to somebody at Wufoo, I will guarantee you that they will find an option to spend $500,000.

Maybe it’s we send a trainer and teach everyone how to use their drag and drop form‑building interface, and then the cost of the trainer’s time is $500 an hour, and the business will say, “Oh sure, yeah, whatever.” By the way, you need to purchase a service level agreement with them, and the service level agreement runs $20,000 a month, and there are businesses that will happily pay that.

Software‑as‑a‑service economics 101, why do you want to charge closer to the top of these pricing points, instead of the bottom of the pricing points? Because you have to get a lot less customers to generate the revenue that you want, to either replace the day job, or to meet whatever your own personal goal is. How do you segment plans? First, align it with customer success.

Getting based‑on features can work, but if there’s a numeric thing that allows you to discriminate between customer classes, such that the more value they get out of the product, the more X number that they need, segment primarily based on that X number.

It doesn’t have to be linear segmentation, because the ability of Fortune 500 companies to pay is not linear, with respect to the size of the company. A 1,000 person company is not the same as collecting 1,000 one‑man companies and putting them all in a room together. They have orders of magnitude more money, so you should probably be charging them orders of magnitude more money.

“Names matter.” Back in my time as a Japanese salary man, I was given a project to run by my boss, and I was trying to buy, I think, “Crazy Egg” for it. I did the projection, I wrote up the proposal for my boss, and said, “By the way, we need the $9.99 hobbyist Crazy Egg plan, and could you please approve the purchase for that?”

Boss takes my printed out proposal for the project, looks down at “Hobbyist,” goes over to crazyegg.com, strikes it out in red, writes “Enterprise,” picks the top plan, which was $250 or $500 or something a month at the time, something like a quarter of my salary, and says, “OK, here’s the new proposal. Sign off on it, and then I’ll sign to my boss.”

I said, “Boss, boss, we don’t need the enterprise plan, our projected traffic is clearly under the hobbyist plan.” He says, “F if I’m going to tell my boss that I want a reimbursement request for the hobbyist plan, so we are under the enterprise plan.” I was like, “Can I get the enterprise salary?”

[laughter]

That did not work out so well. That’s why I no longer work there. Anyhow, feature segmentation can work, particularly if you have features where there’s a hard requirement among some customers, that they must have a particular feature. That segments people into, “Has a little money” vs. “Has a lot of money.”

For example, healthcare in the United States has more money than God, and something that a lot of healthcare customers are going to be very particular about is, “Is this HIPAA‑compliant?” Talk to me later if you want the full story on that one, but the magic words, “Is this HIPAA‑compliant?” means you can charge them as much money as you want. [Patrick notes: The one-sentence explanation: Healthcare providers in the US are obligated to follow the Health Information Privacy and Availability Act to safeguard patient health information, which imposes some technical and process safeguards on anyone who handles most data for them.]

By the way, you can have a system where all accounts are actually HIPAA‑compliant, but you only tell people that the most expensive plan is HIPAA‑compliant. Because they’re not actually caring about HIPAA‑compliance, they’re caring about being able to sign off on the fact of HIPAA‑compliance. If you simply refuse to sign off on that fact for anything that costs less than $1,000 a month, all of your healthcare clients are going to go for the $1,000 a month plan. Which is, by the way, nothing in healthcare.

The Most Important Pricing Advice Ever: Charge. More.

Charge more, charge more, charge more, charge more, charge more. Anyone have a question about pricing? You should charge more. You’re probably ridiculously underpricing. $4,000 a month is the cost of the cheapest possible employee, you are less than a tenth of that. You are probably creating a lot more value than many employees in the organization, so charge for the value you are creating.

I was doing tear‑downs earlier. Here’s what I put up for my pricing grid about a year ago, and since I haven’t had all that much time to work on “Appointment Reminder,” I made a lot of mistakes. I haven’t fixed them yet, so I’m going to tear‑downs some of my own pricing grid. [Patrick notes: Compare and contrast this slide with the current version.]

I have a $9 a month plan. That was a mistake. I actually have a lot of customers on the $9 a month plan. They account for about 80 percent of my customer support requests, and approximately 95 percent of my headaches, and they pay me approximately nothing, and don’t stick with the service for very long. [Patrick notes: When I did the math recently, customers on the Personal ($9) plan had a churn rate which was literally double that of the Professional ($29) plan, meaning a single signup on Professional was worth more than 6 Personal signups.]

I have an enterprise plan that’s coming soon, any day now, a year later. [Patrick notes: Appointment Reminder closed its first Enterprise account a few weeks after Microconf. If you want to hear about this topic in a lot of detail, I talked about it at a presentation for Twilio several months later — I’ll post it in a week or two.] There’s actually a plan that isn’t even on here. It’s $200 a month, I call it “Small Business 2,” because I’m very creative like that. It’s just small business, and I bumped this number up a little. Small Business 2, plus Small Business, create over half my revenues that are based on this plan. Oh, quick update on “Appointment Reminder,” it quadrupled in a year without me doing much work on it at all. Thanks. End story, just make systems that really help. A tactic you should all probably steal.

The Tactic All The Savviest Software Companies Use: Automated Marketing Email

Can you raise your hands, everybody? Just get a little stretching. Put your hands down if you have not emailed a lot of customers all at once this month. If you look around the room and you’re looking for speakers, you will find almost all of the speakers still have their hands up, and this is one of the things that consistently segregates the really savvy people from people who are not quite at that level of savviness yet, so of course I didn’t really seriously start collecting emails for six years.

This guy Ramit Sethi, one of the smartest people on the Internet in terms of marketing, he says “The one d’oh moment is that I was not building up an email list.” You heard earlier about an email list is creating your own recurring stream of earned media, because they are people who want to hear what you have to say. They trust you on a subject, and they are begging you to sell them on your solution, so you should be getting those emails. Let’s talk about how.

Why does email rock? Some people, because we’re all techies, might say, “If I want to get in touch with someone about a new blog post that I wrote, there’s RSS feeds for that, right?” Email is like RSS, except better in every possible way. Email is actually read. RSS is not read. Quick show of hands, who here is over 10,000 unread items in their Google Reader? [Patrick notes: Dramatically less people than when I delivered this talk, I would expect. </rimshot>] I rest my case.

Email is actually read by real people too, and by “real people,” I mean folks who don’t come to conferences like this, and who have authority to sign off on $500 a month purchases without breaking a single sweat.

Email is a necessary time, whereas RSS reading is, “I don’t have anything important to do today. If I don’t have anything important to do I might read some RSS stuff,” whereas emails, if you’re an information worker like all of us, email is your job. You live in your inbox. Many, many things in the inbox get read, particularly when they sound interesting.

The psychology of email is really important. If I put a diamond in a trash store, you’re probably going to think that diamond is not worth so much. Think of the things that will be around your message in somebody’s inbox. It will be a lot of important work. If that’s all important, your message is probably important as well. Think of the things that are probably going to be around your blog post or content in someone’s RSS feed, or someone’s bookmark manager.

It’s probably going to be a lot of commoditized Internet dreck that they’re going to get to the first day after never. [Patrick notes: The following is a little brusque for my typical humor, but was an in-joke for attendees of Microconf from the previous year, where Hiten Shah and I had done live analysis of websites of several attendees. One had a bookmark manager system with a bovine theme.] If you do free association for, say, “What’s the spirit animal of email?” It’s Thunderbird. It’s fast, it’s powerful, it does important shit. If you do free association with, “What’s an animal we can associate with bookmark systems?” What would it be, a cow? It’s fat, it’s stupid… it shits.

[laughter]

Do email instead. When I say “do email,” what do I mean? Really simple. Collect their email addresses, educate them over the email, and then sell them stuff. Let’s go into detail on that. For a successful landing page, you really only need a few things. Just ask for the minimum possible information from them.

Probably their email address and their name, because everyone likes hearing their name, and you should probably put it in subject lines, because that’ll increase open rates on your emails quite a bit. Give them a nice, attractive button that promises value, not pain. Get something cool. Does anyone here run a website for sadomasochists?

[laughter]

There are no hands up in the room, which means that nobody should have “Submit” as the text on their email button. [Patrick notes: I use this line because it is punchy and inevitably gets a laugh, but seriously, you can pick up totally free double digit improvements by switching to [Get My Free Guide] or similar benefits-focused copy. Try it in an A/B test if you don’t believe me.]

[laughter]

Minimize distractions on that page. You generally don’t want to be collecting email from your home page. Why? Because your home page has to serve many masters. You’re probably trying to get people into the trial, get them into the pricing grid. You should generally be collecting email on dedicated landing pages. What will you have on your dedicated landing pages? A sweetener. Because people don’t really care about you, they care about themselves, so tell them that giving you their email will accomplish something for them. Let’s go into ways to do that.

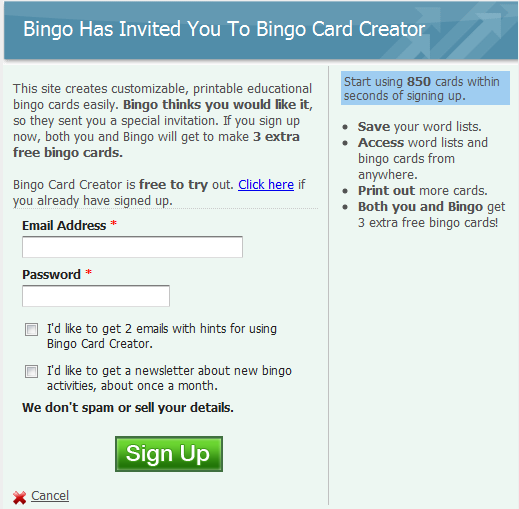

The simplest possible way to get permission from someone to send them email is when they’re signing up for the trial, say, “Hey! In addition to that trial, can I send you email?” Just takes adding one box. Downside, it’s going to minorly decrease your conversion rate to a free trial. Upside, you’ll get crazy conversion rates on this. By the way, who here hates email, and thinks, “Man, I hate getting email. I would never click on ‘Yes, I want to get email from you.'” Yeah, hands up. Real people don’t hate email. Some people like email a lot.

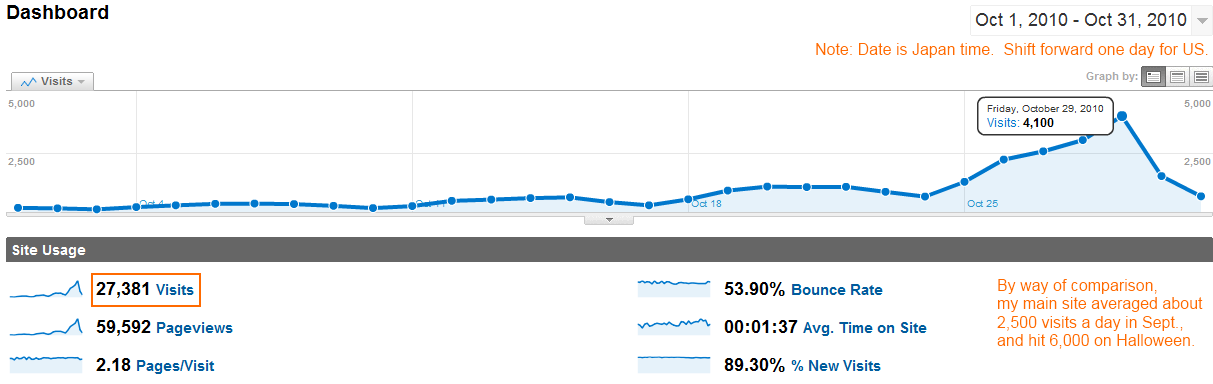

I have a newsletter that goes out to the bingo card people, and it goes out about monthly. I sent it out for October and said, “Hey, Halloween bingo cards! You make them by going to Bingo Card Creator and typing about Halloween stuff!” Then the November email is, predictably, Thanksgiving bingo cards. “You make them by going to Bingo Card Creator and typing about Thanksgiving stuff.”

I didn’t hit the “Send” button on the November email, because I just got busy that month. I got three messages from teachers in America, all of them saying, “Hey, I didn’t get the email from you in November. I must have missed it or something, or it got eaten by the Googles.”

[laughter]

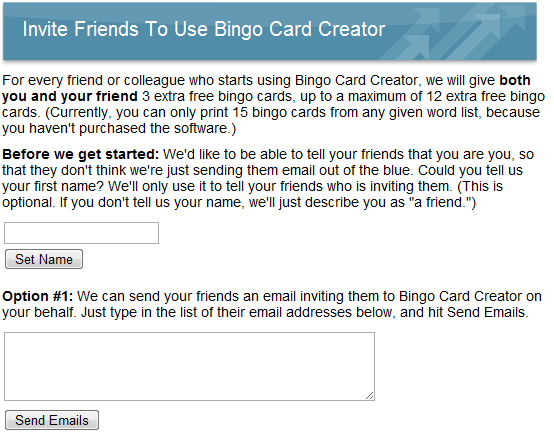

“Can you please send me the email for November?” I wrote back, and I said, “There just wasn’t an email for November, because I got busy, but it was just going to be about Thanksgiving stuff.” They’re like, “That’s sad! I want to read about the Thanksgiving stuff?” Whoa! Missed opportunity. A better way to do things than collecting emails with your trials is to create some specific incentive. For example, Ruben from Bidsketch uses beautifully designed templates of proposals, and says, “OK, I will give you a beautifully designed template of your proposal.

You can turn around and make this into money, and all you need to do for that is to give me your email address, so I can email you a link to it.” Works very, very well. You can see incredibly high conversion rates to this, and the people who convert to, “I care enough about beautifully designed templates to give an email address, just to get a link for a download link for them” are not the kind of folks who hang out in Hacker News like it’s their job. It’s the people who really care about this. They make really great prospects for selling to. Third way…

Male audience member: [Paraphrased] That doesn’t mention that he’s going to send you an email, though. Isn’t that a no-no, permission marketing wise?

Patrick: I think it actually does, I just cut it off with the screen grab.

Male audience member: OK.

Patrick: A different way, and this has vastly higher development costs, but you should consider doing it. Make a one‑off tool, gate access to the one‑off tool based on giving your email address. For example, WP Engine does this kind of well. [Patrick notes: See here. Disclaimer: client.] They have a tool that will tell you if your website is slow, and it takes a few seconds to run and whatnot, so rather than just doing Ajax refresh, they’ll say, “Hey, we’ll send you a link to your report when it’s ready,” and they give you a little option there. “Hey, in addition to hearing whether if my website is slow, I’d also like to hear a one‑month course about how to fix that, and make it more scalable, make it more secure, and whatnot.” Get Jason drunk later, and ask if this works or not. This sort of thing can provide very focused, valuable leads for you, and it’s like a great transition moment into the first couple of emails from you. Let’s talk about that.

There’s a cycle here, of how sales‑y you get. Someone’s coming off the Internet, they don’t trust you, they don’t know you from Adam. For your first couple of emails over the course of a month, and you might send six emails or eight emails over the course of the month, depending on how much of a high‑touch complex sales process your service requires. For the first couple of emails you focus on trust building and education, and that’s it.

If you were just talking about someone’s website is slow, say, “Hey, thanks for signing up for the WP Engine one‑month course on improving your WordPress site. Here’s three ways you can make your website faster.” Very focused on value for the customer. Minimal, if any, sales content for WP Engine.

Then, over time, as you have built up credibility with the customer over three emails, they’ve seen your name in their inbox, they’re starting to associate it with your problem domain, and they’re getting value out of it, you start getting a little more sales‑y, and you push up that sales‑y to the maximum point. Then if they don’t buy it by the maximum point, they’re probably not ready for your offering. Back down a little bit, go more on the education again, and then try it again, but sell a different product offering. For example, a different plan.

I just threw up a random thing here for a template for an email that educates someone about something. It’s not really rocket science, it’s the three‑paragraph hamburger essay that you all learned to write in sixth grade. I hesitate to say this, but don’t be afraid of dumbing it down too much. You all live in your problem domain many, many hours a day, for months, weeks at a time.

Most of your customers are not super‑awesome ninja rock star experts at your problem domain, so teach them the basic stuff, because most people in your problem domain are beginners or intermediate, not super experts. Feel free to share of your knowledge, and answer basic questions that they have, and then at the end, just say, “Hey, do you have a question about this? Send me an email. I read all of them.”

Almost none of you have less than hundreds of thousands of customers, would feel any burden from getting email back from this, because most people think, “Oh, he doesn’t really mean that.” In fact, you will get emails saying, “Do you actually read this?” and then you fire back, “Yes! Signed, CEO.” I guarantee you if they have money, you’ve just got a customer for life. Even if you have hundreds of thousands of customers, like this for “Bingo Card Creator,” the email load is manageable, and you can give options for more and more things to do to convert.

When you’re getting into sales‑y hump on the graph, what do you do? First, you eliminate all decision making that they need to do, aside from, “Do I accept the offer, or no?” which means, if you have four plans, you don’t say, “OK, go to the pricing page and pick which of the four plans is worth it for you.” No, give them a recommendation.

Say, “Most of our customers find that this is the best value, you should buy this. Here’s the reasons why you should buy this. It will solve your problems, it will solve your problems, it will solve your problems, your life will get better, your problem’s solved. You, you, you, you, you, you, you, you.” Offer them a time‑limited bonus. “Yeah, you could have gotten to that pricing page at any time over the last 365 days, but if you take me up on this offer in the next seven days, I will give you something cool.”

It’s up to you what that something cool can be. For many of you, assistance directly from the CEO in integration is a really compelling offer, because wow, you can’t get that anywhere else. Wow, their perceived value for that is very high, and it immediately addresses one of the objections that they have for using your software. It’s like, “Oh god, I have to integrate that. I have to copy‑paste scripts into my web page.”

We’ll do the copy‑pasting for you, and thereby earn your loyalty for the next several years, and several thousand dollars of customer lifetime value, and it will actually be done by a freelancer that we’ve hired and told them how to FTP stuff. I think I stole that one from Rob, works pretty well. Pre‑answer all of their objections in the email, and on any page that you link them to. This is what we were talking about earlier in the tear‑downs.

When you’re talking to customers, you’re hearing their objections, “The price is too high.” Find the customer testimonial that says, “Oh yeah, I winced, but man, it’s so worth it,” and put that right on the page about answering the pricing objection with, “OK, here’s how you calculate the value for this. It’s a screamingly good deal for you. It will save you hundreds of hours of employee time, for only tens of thousands of dollars.” How do you learn about writing email and copy‑writing better? I suggest signing up for a lot of email and getting it from people, because they will convince you to buy all sorts of stuff.

Seriously, Ramit Sethi, did a call out to him earlier, he is a genius at this. He’s a friend of mine, I know he sells info courses for a living, and I’ve never bought an info course on anything. I was reading his email, I sent him an email at the end of it, because he says, “I respond to all of my emails.” I’m like, “Hey, Ramit, this is Patrick. I would crawl over broken glass right now to hand you my credit card. Wow.” Seriously, get his emails. They’re good stuff.

In addition to teaching you how to write email better, they are genuinely worth your time if you’re concerned with increasing your career and/or freelancing business. The Motley Fool does investment advice. It’s bad investment advice, but they sell it really, really well. For any sort of scummy market, like online nursing degrees or anything, people who are paying $100 plus just to get an email for that, probably know what they’re doing or they would be bankrupt already. See what works and use your powers for good, not evil.

Improving The First Run Experience Of Your Software

[Patrick notes: If you’d like to hear me talk about this in a lot more detail, go to training.kalzumeus.com and give me your email address. I’ll give you a 45 minute deep dive into this topic, totally free.]

More specific to software people, let’s talk about the first‑run experience of your software. Hands up, who here knows how many people come back to using their software after the first time, like that is something we check? OK, there’s a few hands going up here. Almost everyone should check that.

For those of you who aren’t checking it, I’m just going to tell you the numbers right now. It is between 40 and 60 percent of people come back after using it the first time. Which, subtract from 100, 60 to 40 percent of people never use the software a second time, because they did not perceive much value in the first‑time use of your software.

They got bored of it after 10 seconds, or within five minutes, so you should make that first five minutes of the software F‑ing sing. It is the most important five minutes in your lifetime, because every subsequent use of the software is gated based on surviving that first five minutes that most of your users are not surviving right now.

Can you just show your software here? Who here thinks that this is a fun first five minutes for software? Microsoft can get away with this, because your first five minutes with using Microsoft Word were probably in 1992, and you had to do it to pass a class, and Microsoft is Microsoft, and you absolutely have to use this if you want to work in the information economy, but it’s kinda sucky.

There’s just so many options here, it starts you with a blank screen, and you have no clue. If this was a free trial product, what do I do to get value out of Microsoft Word, to make the decision on the go or no‑go for buying this? Microsoft, that isn’t really a problem, because you’ve already bought this if you’re seeing this screen. If this reminds you of your software at all, if you drop people into a blank screen, that is a huge failure mode. You’re going to fix that. How?

You script their first five minutes like it is the invasion of Normandy. “You are going to do this, and then you are going to do this, and then you are going to do this, and then you are going to do this, and then you are going to be F‑ing happy.” Can I give you a great example of that? Who here has played “World of Warcraft?” OK, a few hands. Who here managed a raid guild in “World of Warcraft” for a few years? OK.

The first five minutes of “World of Warcraft” is literally, you talk to this guy, there’s a big exclamation point on his head, and it says, “Right click the guy with the big exclamation point.” You right click him, and he says, “You need to save the world from a wolf. There’s a wolf behind you, you can kill it with Z. Z! Z! Z! Z! Z! Z! Z!” So you Z, Z, Z, Z, Z, you kill the wolf, you go back to the guy, he’s got another big exclamation point, you right‑click, because you’ve learned that that works in the world.

He says, “Great job! Save the world, there’s 10 wolves, kill them! You get Z and X this time. ZX! ZX! ZX!” So you ZX, ZX, ZX, and you have a feedback loop where it’s both teaching you on how to use the software, and you feel like, “Yeah, I’m the powerful level one gnome mage that’s has got to spend the next 3,000 hours of my life playing this game,” but it’s a great, awesome experience for you.

At the end of five minutes, you’ve accomplished something, and you’ve learned how to use the software. All of your software should be that addicting. Sign up for the free trial of “World of Warcraft,” play the first five minutes, then stop!

[laughter]

You measure their activity, then you use A/B testing, like we talked about last year to change their activity. This is where the growth hacking comes in, and making sure the designing of their first user experience with the software is actually motivational. Here’s the, “If you’re going to do this, then you’re going to do this, then you’re going to do this, then you’re going to do this” funnel for “Bingo Card Creator,” instrumented out in KISSmetrics, which is, by the way, the way I would go if I had any budget at all to spend on it.

I don’t know what I spend on it, it’s probably like $150 a month, or, you know, nothing. [Patrick notes: I literally was unsure of this until I checked with my bookkeeping software a moment ago. It was indeed $149. Relevantly to other SaaS businesses: what does this suggest about the resistance to spending any figure between $50 and $500 at my business? Right, I don’t care in the slightest. So charge me closer to $500 than you do to $50. If you provided as much value as KissMetrics does I’d pay without a second thought.] You can write arbitrary code to do something like this, and just throw it into a file if you need to. You can see here where people are falling out of the funnel, if you’re into Bingo Cards, like that’s your life, and you can try things to get them to actually work.

I don’t really have enough time to talk about what really worked here, but the punchline here is that a particular intervention increases the amount of people who successfully get through to printing a bingo card with “Bingo Card Creator” by 10 percent. From 60 percent to 70 percent, which is really powerful for me.

If you read my blog, I’ve blogged about what exactly this was. It actually didn’t increase sales, weirdly enough, but similar things that I did with only two hours of work increased sales by 16 percent for two hours of work, durably. About tens of thousands of dollars for two hours of work, very motivational, you should probably do it. You fix the weak spots in the funnel that you’ve identified, once you have the funnel‑analytics in.

Here’s just some examples of things that work for Bingo Card Creator. Probably not too motivational for you, but they paid for my wedding, so motivational to me. Dan gave a great example earlier in the Growth Hacking talk [Patrick notes: Dan Martell’s talk is available here], about people that have just signed up, and they can tweet something, but they weren’t really planning on tweeting something, and they don’t know what to tweet so they don’t tweet, and then they go away and never use the app again.

You say, “Hey, you should tweet something right now. Let me give you 10 suggestions. Pick which one you like.” From six percent of the people went through and actually tweeted something, to 70‑plus percent of people tweeted something, which is a huge, epic win in activation. “Activations” means happy use of the software. I guarantee you if you haven’t optimized this at all, you can achieve extraordinary gains in activation for not all that much work.

The thing that worked for Appointment Reminder was implementing a tour mode. What’s a tour mode? Appointment Reminder has sub‑optimal things about the way the market uses it, in terms of getting people through their 30 day free trial. I actually collect credit card at the start, and then they get 30 days to decide whether they want to cancel or not. The problem is that people typically make their appointments for the customers well in advance.

By the time the 30‑day mark rolls around, Appointment Reminder might not have actually reminded a single customer about appointments, because they were scheduled that far in advance, so that’s sucky. They get to the last day, they get to the email, it’s like, “Hey, we’re charging your credit card in 24 hours. If you don’t want that, cancel.” They think, “Oh, this hasn’t really done anything for me, cancel.”

Rather than making it take six weeks for them to perceive value from Appointment Reminder, and to have people come in to their massage therapy practice, or whatever their business is, I wanted to expose that value to them in the first five minutes. So I dragged them by the nose through using the software. Instead of calling their customer, I made a special little mode that would call them instead, and say, “Hey, this is your fake appointment reminder. If you actually had an appointment, it would be five minutes from now. Click ‘1’ to confirm it.”

Bing, they click ‘1’. “Great. That’s the experience your customer gets, now let me show you how to do that generally.” It walks them through this crazy, obtuse interface, because I’m not an interface designer. Says, “Yeah, put in (555) 555-5555 for one of the clients, and we’ll schedule an appointment for them.

It walks through every step of the work flow, and tells them, “OK, and this is where someone might actually cancel your appointment. Normally that sucks, but we’re going to send you an email, and that’s going to make you money. Isn’t that great? You’re having fun now.” Tell people they’re having fun now. That’s a big secret in Vegas. I bet there’s people running around in skimpy dresses with a lot of alcohol in their hands, trying to tell you all the time, “Hey, you’re having fun! Hey, you’re having fun! Hey, you’re having fun!”

Because if you tell people they are having fun and getting value from the software, they will tend to believe you. Create value, but also tell them that you are creating that value. If there is a social or viral component in your software, if you tweet about using the software, if you invite your friends, if there’s some sort of friends‑list management, first you should probably pre‑populate that friends list using anything that you can possibly do, because people hate managing friends lists.

Make sure that that goes in in the first five minutes, because it will greatly increase your viral factor, and that literally makes or breaks businesses. Zynga obsesses about this. Not a win for the world. Dropbox obsesses about this, that was a win for the world. If, on the other hand, your software requires a lot of data entry, like you’re mocking up things, or creating documents, or making bingo cards for people, figure out a way to eliminate the data entry as a prerequisite for actually getting the fun use of the software.

Maybe give them sample templates that they can use, or just put in fake data, and give them a “Blow away the fake data” button. This is a very deep topic. I have a 45‑minute deep dive available at training.kalzumeus.com. I’ll tweet a link to that later. If you give me your email address, you can download the video at any time. I’m actually not trying to sell you stuff. In fact, when I actually have something to sell you, send me an email and say, “I was at Microconf,” I’ll give it to you for free.

A Brief Digression Into The Scintillating World Of Running A Software Marketing Consultancy

Patrick: [After consulting briefly with the audience, I decided to talk about consulting for a moment.] What do I do? We talked about this earlier, the way to extract money from any company is to promise them one of two things. Either you’re going to increase their revenue, or you’re going to reduce their costs. I’m kind of terrible with firing people, and that’s the best way to reduce costs for most software companies. But I’m kind of good at scalably increasing revenue, so that’s what I do. By trade, I am a programmer. If I was less savvy about this, I might describe myself as, “I’m a Ruby on Rails developer who knows a few things about a few things.” Ruby on Rails developers might be hard to hire right now, but they’re hireable. If you have $200 an hour, you can find Ruby on Rails developers. But don’t compete with all the Ruby on Rails developers in the world, because Github is lousy with them.

Instead, say that you are giving an offering that will increase their revenue by a lot. I can point to particular customers of mine, that they will find very credible within their space, and say, “We worked with Patrick and then our revenue durably did a stair‑step function.” I said, “What is stair‑step 100 percent increase in sales of your software as a service product worth to your company, if you have $10 million of sales right now?” “Oh, that would make our sales $20 million.”

“Oh, great. Then I’m pretty cheap compared to the $10 million marginal revenue you’ll get,” and you get very little push back on prices, no matter how much you bump it up. Scarily low. Yeah?

Male audience member: When you make that sale, how do you guarantee it, or say, “If I don’t reach this, you don’t pay more than that,” do you know what I mean?

Patrick: No. [laughter]

I’m sufficiently credible about this thing. I think most of my customers actually succeed, because most of them invite me back. Let’s say a week of my consulting rate is similar to the fully‑loaded cost of hiring an engineer for a month. [Patrick notes: That was a good ballpark figure a year ago. My consulting rate tends to increase over time as I get more successful engagements to use as references, get pickier about what clients I take on, and just start writing higher numbers on proposals.] If you have an engineer work for you for a month and the product fails, like most products do, the engineer doesn’t give his salary back, right?

Plus the pricing structure would be very radically different if there was downside to me, if it didn’t work out. If there’s downside to me if it doesn’t work out, there should be substantial upside to me if it works out, so if I double the sales for the company, I think as a close approximation I should own half the company afterwards. I’ve actually used that line on people before [Patrick notes: In case it is not obvious, no well-run company anywhere would even consider that payout structure], and they’ve been like, “Oh, that’s cheeky! But we’ll go with the cheap option.”

[laughter]

Where the cheap option is $20,000 a week, or whatever. That is just a representative number, that is not a quote.

[laughter]

How did turning down $700,000 work out? I went to a company in a far‑off land, which is not the United States, because the United States is a far‑off land for me, but a different far‑off land, and I did some stuff. Can I talk to you about what the stuff I did? Hmm. I can’t talk about specifically what the stuff I did, but if you’ve listened to my conference presentations or read my blog, you know that I really like A/B testing, and I really like Search Engine Optimization. I really like, say, designing the first five minutes of software, and I really like, I don’t know, redesigning purchasing pages to extract more money from businesses that don’t care about how much money that gets extracted from them.

I did some combination of those things for a particular software company, and made them a lot of money. A company that was making X, so say eight figures of revenue, went to a different eight figures of revenue. But there’s a lot of play in the eight figures range.

[laughter]

That was after working for them for two weeks. The CEO said, “Hey, at the rate…” It’s kind of embarrassing for me, but the rate I quoted them was $20,000 a week. Why am I embarrassed? Because part of me has always thought that I’m really not worth that, and I’m just good at bamboozling people. [Patrick notes: Nagging doubt monster!]

[laughter]

This engagement was the one that turned it around, because one of the things I generally insist on is, “OK, I like this metrics stuff, I’m going to get metrics for the before and after. We’re going re‑test, and we’ll see if this actually worked.” We came back two weeks later and we looked at the metrics, and I’m like, “Oh, I must have mis‑implemented that,” and he says, “The bank account disagrees with you.” I’m like, “Oh, oh, wow. Oh, wow. Oh, wow. Oh, wow.”

He said, “So, what was it? $20,000 a week, or whatever we’re paying you?” A CEO doesn’t even know, that’s not a motivational amount of money to a CEO at an eight figure‑a‑year company, despite the fact that it’s kind of a motivational number for me. He said, “What was it, $20,000 a week? So if you consult 50 weeks a year, that’s a cool million.

“But you can’t actually consult 50 weeks a year, so there’s overhead and whatnot, and you have downtime, and you have to go to conferences to meet people like me, so let’s call it a 30 percent haircut to that, so that would be what, $700,000? Is $700,00 a motivational amount of money to you?” [exhales loudly] I’m like, “Wow, wow, is that on the table?” It’s like, “I’m the CEO, we’re sitting at a table, bam!”

[laughter]

My life flashed before my eyes, and I’m like, “Wow! Wow! Wow! Wow! No, Wow!” I guess the follow‑up question to that is, “Why did I say no to that?” Consulting is the right thing for me right now. I have a wedding to plan for, I have two weddings to plan for, one in Japan, one in the US. People with iPads are successfully convincing me that I’m probably still in your position, but for the consulting business.

I’d love to help you by coming here and spreading knowledge, and talking to you, and taking your emails any time my email is up on the screen. Doing it as a day job again is not something that’s motivational for me, even for more tea than there is in China, I think is the expression. $700,000 is a lot of tea!

[laughter]

Patrick: Sorry, not meaning to brag there. OK, questions?

Rob Walling: Can we get a round of applause first? [applause]

[Patrick notes:

My recollection is that I said something here which unfortunately did not make it on the video, but it is more important than the rest of the speech put together, and since this is my blog I think I’ll take a moment to say it again. All the speakers at Microconf, and many of the attendees, receive substantial support from their spouses and families, both in the sense of “Hey honey, can I fly to Vegas to talk with some quirky software people?” and in the day-in-and-day-out support for the entrepreneurship career choice. That’s sometimes risky and sometimes involves annoyances to families that people don’t generally have to deal with when their spouse is in 9-to-5 employment, in everything from quirky hours to weird comments from friends/family to the inconsistency relative to biweekly paychecks. We should recognize the support of our families as being instrumental to our business/careers, and also keep in mind that they are, ultimately, stakeholders in the business, with a claim superior to even employees/investors/customers, because at the end of the day they’ll be with us when the business is, as mentioned earlier, but dust and memories.

The attendees at Microconf joined me in giving a standing ovation to the (numerous) family members who had made it out for the conference, and also for the folks who were supporting attendees from home.]

Recent Comments