Author’s note: This post is gigantic — over 10,000 words. I don’t recommend reading this in one sitting — bookmark it and come back later.

//

Early this October, I was privileged to attend the Business of Software conference as both attendee and a speaker (see disclaimer waaaaay at the bottom of this post). It was far and away the best conference I’ve ever been to. You should go to it next year — I know I will, if I have to swim from Japan to Boston to do so. (If you would like to but don’t think it is possible, see waaaaay at the bottom of this post.)

The featured speakers were, virtually without exception, remarkable. The 7.5 minute Lightning Talks (one of which I presented — more about that after they post the video, you will be amused or your money back) were often entertaining and at least a few of them were packed with better detail than 15 Powerpoint slides have any right to be.

The phenomenal content of the conference, however, is just an excuse to get a few hundred ferociously smart people in the same hotel for three days. I got to finally meet in person a few of the folks who either personally assisted me in my early days as a businessman or have been tremendously influential in my thinking — a short list of shoutouts includes Ian Landsman, Dave Collins, Joel Spolsky, Eric Sink, Eric Ries, Peldi from Balsamiq, and I could put another dozen names here without breaking a sweat. One speaker at one point asked all attendees who had founded a software business to stand at one point, and by my eye probably 60% of the room stood up. During breakout sessions, I heard from everyone from folks doing small software businesses like myself to a company which sells monitoring software for nuclear power plants.

The spirit of generosity at the conference was off-the-charts amazing. However, many conversations were either by explicit agreement or common courtesy off the record — not everybody publishes sales stats, and that is their right — so I’m going to err on the side of caution and only repeat things I learned from the public sessions. That said: beg, borrow, or steal tickets to it next year. I can’t repeat that enough. Although the conference swung to business topics far more often than technical topics, almost everyone I talked to both inspired and holding a notebook full of actionable advice to try.

My notes are incomplete and my memory is fallible, but here were some of the takeaways I got from the public presentations. These are more a combination of my notes and thoughts than transcriptions of what was said. If you want those, wait for the videos to be released.

Seth Godin

Seth posted a riff on his remarks on his blog. The general tone and content was not surprising if you’ve followed him for a while. (If you don’t, do so — aside from being a great communicator, he’s one of the better big-picture thinkers on marketing that I know of.)

Specifically, he says that the software business is undergoing radical changes because technical competence is no longer a scarce commodity: with open source tools, an increasing supply of trained programmers, and the explosion of cost-lowering innovations for creating and marketing software on the Internet, things which were previously the purview of a technical elite are now within what talented teenagers can cook up from their kitchen table. The marketing side of the equation is also changing, since increased crowding means that the traditional model of paying salesmen to push software has devolved into using humans as inefficient spam bots. (See his whole spiel about Permission Marketing here.)

A brief guide to evaluating opportunities:

- Who can I reach with my marketing message?

- Will they talk to people on my behalf?

- Can I earn and maintain permission to continue the conversation with them?

- Will they pay for my solution to their problems?

Perceptive readers will note that technical difficulty appears nowhere above.

Best four words of talk: “Ideas that spread, win.” Software is now about creating a tribe or otherwise achieving leadership of one. Take AutoCAD, for example: it isn’t a product, it is a movement: we architects who use AutoCAD are here to change the industry away from using pencil&paper drafting. You are either in the movement or opposed to it, because it is an existential threat to your business, but you certainly aren’t neutral on the question. Boring software creates no movements and has to be sold the old fashioned (expensive, ineffective) way.

Another example of movements is the trend towards measuring things, which was a recurring theme during the conference. Toyota succeeded in changing the face of manufacturing because they got religion about statistics, and a similar sea change is finally happening in software. This meta-trend is creating a lot of extraordinarily valuable companies directly and also making the rest of us leaner and meaner. (Bingo Card Creator has a more sophisticated approach to metrics than many Fortune 500s. That’s a shame, but also a tremendous opportunity for smart, savvy software firms.)

I was quite amused by a throw-away example of the difference between capitalists and socialists inspired by pin-making machines: prior to the industrial revolution, it took a skilled artisan a day to hone 5 pins (small bits of metal which one uses to, e.g., attach fabric to each other) by hand. A pin-making machine lets any 5 people who can be trusted to learn a simple, repetitive set of instructions make 10,000 pins a day. Socialists hearing this thought “Oh no, that is going to totally destroy the livelihood of pinmakers.” Capitalists hearing this thought “Memo to self: be the guy who owns the pin-making machine.” As the cost of software approaches zero, you want to be the guy who owns the machine.

Relatedly, with regards to your future employment prospects: draw a Venn diagram of job skills you have and skills which can be automated (or, by extension, anything which can be adequately explained by any amount of writing on paper, because anything that can be written down can get shipped to India). Anything in the intersection represents career suicide.

Seth claims that no “competent” people work at his current software company, Squidoo, because “if we only needed competency, we can get that from [outsourcing]”. You hire exceptional people and let them execute on things which require exceptional talent, and write down things which only require competency. Low-wage grunts can do the competent stuff. “Your job is a platform, not a list of tasks.”

Some personal thoughts: Seth was bearing on charging for software because of competition from OSS competitors, preferring instead to lead movements where joining was free (to maximize the size of the movement). Happily for those of us who sell software, almost all OSS projects are incompetent at marketing, which matters more than technical execution. Seth gave an example of trying to sell water: what are you going to do, make water wetter? That is a wonderful example, since bottled water didn’t exist as a category 50 years ago and sales are going up every year, over a century after America solved the problem of giving everybody what amounts to free, infinite, drinkable water. It amused me greatly to hear that bottled water was going away while attending a conference at a luxury hotel which sold $4 bottles of bottled water placed in the restroom literally next to the tap of ever-flowing unmetered municipal goodness.

David Russo

David gave a presentation about hiring at software companies, in particular about hiring to create and sustain a corporate culture as the company approaches scalability. I regret I was insufficiently attentive during it, as this topic is several years ahead of need for me.

Briefly, there are five models for corporate culture in the literature:

- Bureaucracy (the traditional BigCorp model)

- Autocracy (Apple-style, where the company is an extension of the Will of Jobs)

- Engineering (Google, where the engineers run the asylum)

- Star culture (a large consulting firm or, perhaps, 37Signals, where individual contributors are expected to be stellar and you can put up with rough edges because, hey, rockstars)

- Commitment — a consensus culture with loyalty receiving strong priority (and, as you can probably guess by position on the list, the clear favored choice of the presentation)

There was an example of Westinghouse having a non-engineering CEO who proved to be disastrous for the company. Afterwards, the board resolved never to hire a non-engineer again, because the culture of Westinghouse was ferociously engineering-dominated and when engineers talk to each other they break out the secret engineer decoder ring. The CEO, who couldn’t speak the language or achieve respect among the engineers, was sidelined and failed at achieving his objectives.

Culture generally grows organically out of a business rather than being imposed from the top-down. Changing a firm’s culture midstream is very painful, and Harvard studies suggest it has quantifiable negative impacts: 50% reduction in odds of an IPO, tripled likelihood of business failure, and 3% less growth monthly. (The engineer in me winces at the compounding there.)

David’s advice was to invest in employees: hire brilliant people, and let them be brilliant. The outcomes they achieve are more important than the work itself.

Dharmesh Shah

Dharmesh is CEO (most recently) of Hubspot, a marketing tool for small businesses. They have raised quite a bit of money and, more importantly, have a lot of paying customers, consistent growth, and a revenue curve which virtually defines “up and to the right”. You should be reading his blog already.

He presented a few techniques from Hubspot which were “interesting and not obvious”. For example, successful SaaS companies which IPOed had a median capital raise of $42 million dollars. It doesn’t match with our expectation that you can make a SaaS startup in your garage, partially because SaaS companies essentially offer their customers upfront financing (by spending their cost of customer acquisition in a front-loaded fashion and then recouping it over the 4-5 year lifespan of that relationship).

A key metric to keep track of: customer churn rate, because a 50% decrease in it doubles customer average lifetime value (LTV). One of Dharmesh’s periodic hobbyhorses is that if you know LTV and know the cost to aquire a customer (CAC), then if CAC is less than LTV by a fair bit, you take as much investment as humanly possible, spin straw into gold, and walk away with money hats. (This is far and away the best pitch for a software company taking VC money that I’ve ever heard. See also the video of him speaking last year, if I remember right he covers it there.)

There are a few ways to measure churn: as percent of customers, as percent of revenue (better accounts churning faster than entry-level accounts: uh oh!), and “discretionary churn”, which is churn among accounts who are actually able to make the decision to cancel and are not, e.g., locked into a one-year contract with you at the moment. However, overoptimizing on churn rates is myopic, because absence of churn does not indicate the presence of delight, and customer delight is a key to long-term success at marketing the product.

One particular way Hubspot maximizes for customer delight is by creation and use of a Customer Happiness Index (CHI), which is a backtested predictive measure of someone’s likeliness of churning next month. CHI is dominated by three factors and adjusted as they get more data:

- Frequency of use (more use = less churn)

- Breadth of use (customers who use more features churn less)

- Use of “sticky features” (there exist some features which are so screamingly better than alternatives that a customer who uses and gets value from them is very reluctant to stop using the service)

If I can call out #3 for a moment: many companies I have worked with have “sticky features”, although not all of them know it. (Some day when I don’t have another few thousand words to write I’ll tell you about what they are for Bingo Card Creator and how I know.)

After you have CHI available in a transparent fashion throughout your organization, you can exploit it in a variety of ways:

- Tell your sales representatives to call customers with low CHI proactively and ask them what you can do to make them happy. This simple technique saves 1/3 of canceled accounts, and is virtually free.

- Judge sales reps not just on sales but on CHI of new accounts. (This counters the incentive to armtwist to sell to marginal customers.)

- Judge new features / policies / etc based on their impact to CHI. Concerned about whether charging for consulting for setup is a good play for the business or not? A/B test doing it versus not doing it, and optimize for CHI. (I get the feeling that they might not explicitly be doing A/B testing… but they should be. Sorry, hobbyhorse of mine.)

All meetings at Hubspot include a teddy bear named Molly, who is a stand-in for the customer (they have two customer archetypes: Margaret the marketing director and Olly the owner, collectively, Molly). When they have contentious debates internally, they are frequently decided by someone saying “Hey, what would Molly want us to do here?” Brilliant hack, practically free.

Hubspot sells services, primarily consulting for setting up new clients. This represents a fraction of their revenue — only 7% or so — and decreases their gross margins, because consulting services are intrinsically lower margin than selling software products. But “services are low margin… except when they’re not”: since getting people set up for success increases their CHI and wildly decreases churn rate, selling someone a few hundred bucks worth of engineer time at low margins can lead to thousands of dollars of marginal increase in LTV delivered by high margin renewals of the core product (which has 90+% margins). Star this advice, gentlemen, because it has obvious implications for B2B SAAS startups.

So if you know customers and the company benefit hugely by increasing consumption of consulting services, why charge for them? Answer: perceived value increases consumption, and perceived value is driven by cost. When you give people 5 hours of free telephone support with an engineer, they — being successful businesspeople — find difficulty clearing 5 hours free in their schedule, fail to show up for the call, get distracted, etc. When you charge them $500 for the call, they damn well show up. (Patrick notes: why hello, recent discussion about Chargify free customers and support costs.)

In terms of explaining the value proposition of your software to customers, cribbing from Kathy Sierra: don’t make _____ software, make _____ superstars. Make your customers awesome at their jobs / tasks, and they will pay any price and/or follow you to the gates of Hell.

Hubspot is big about being transparent to a fault within the company, particularly by using a company-wide Wiki which includes financial details, plans, and pretty much everything except salary information. (Apparently, that being public is viewed as possibly toxic to morale without having obvious upsides. Having financial details open to employee audit has obvious upsides: employees can tell you when you’ve let the entrepreneur reality distortion field go wild in the board meeting.)

Best sentence about branding I’ve heard recently: “Brand is what people say about you after you have left the room.”

Eric Ries

I will refrain from giving an in-depth summary of this talk because if you have read his blog you pretty much know the gist of it before. If you haven’t read his blog, start doing so. With the obligatory disclaimer about letting any methodology take over your higher brain processes, the Lean Startup movement (and some of the specific, implementable tactics it suggests) are so effective I sometimes worry about whether established competitors will try to illegalize them. The best effect of this presentation was taking the idea away from the Silicon Valley echo chamber (where “pivot” has become something of a buzzword) and bringing it to an audience of people who largely sell things to people for money, but who still could benefit immensely from some of the Lean Startup lessons.

If you want an hour-long video introduction by Eric to the Lean Startup, you can see parts 1 and 2 of a previous explanation on the Internet.

Some specific lessons I haven’t heard before in a couple years of lurking on his blog or I thought were worth highlighting:

- The key takeaway: Lean Startup matters because the traditional model of development wastes people’s lives. They pour out years of hard-charging startup workweeks making software which doesn’t actually improve the lives of any customer because it solves a problem no one has. This waste of potential is criminal and can be fixed.

- Machine shops and software firms are self-regulating ecosystems if you do them right. For example, if you use continuous deployment and five whys, when you start doing development too fast, you’ll get the brakes applied by having to make investments in quality control repeatedly because you’re making too many mistakes. This lets you find the optimal pace of learning without having to fiat an inaccurate number (“You will write 10,000 lines of code a week!” — which as we all know means nothing, and definitely nothing good) from on high.

- The Agile methodology is a wonderful solution to the peculiar problems of internal IT departments at big companies, where the problem is extraordinarily well-known (“We need our existing payroll system, except on a new architecture where extending it doesn’t require sacrificing goats”) and solutions are unknown (“What is the Rails code to do this?”). It has less to offer startups, where both the problem and solution are unknown. (“Do people even need the thing we’re fumbling forward on building right now?”)

- Since the only people you can plausibly get to use a new product are early adopters, any additional quantum of work done to get the product ready for mainstream users is a form of waste. (This is a bold statement with interesting implications. I’m not sure I agree with it, but it sounds potentially very powerful.)

Scott Farquhar

The president of Atlassian had some thoughts gained from bootstrapping the company from 2 people to a $60 million capital raise and beyond. Regrettably for my notes, this talk was structured as a List of N Things, which ensured that I wrote down N things and grabbed few supporting details.

- Start with 2 founders. For example, when their password database was compromised while Scott was off on his honeymoon in the wilds of Africa, knowing that his cofounder had the situation under control alleviated a portion of the anxiety, and after an emergency flight back to Australia Scott was able to let the cofounder get some sleep.

- You need a business model.

- Dogfood your products.

- Measure everything.

- Always be marketing. Atlassian excels at this — for example, they had a charity give-away where they gave licenses of JIRA (a bug tracker) away for a song to small companies ($5 for 5 licenses or something to that effect), donated the profits to charity, and got massive good press from the deal while also increasing sales in the market segments which drive most of their actual revenue. They also had very appealing marketing of another few initiatives: calling something the Stimulus Package, for example, was an excellent PR hook in the financial crisis environment. I wish I had better notes here. Memo to speakers: please do not autocommoditize your best points by numbering them.

- Your first idea will fail. Atlassian was originally going to market plugins for an obscure product from a company in Europe. It turns out the bug tracker they wrote to make that product was more valuable than the product itself — shades of Fog Creek and CityDesk here. (We heard this theme several times during the conference: Peldi later said that Mockups was originally intended strictly as a plugin for another software, and the standalone version which it grew into now dominates Balsamiq’s revenues.)

- Long term thinking is good.

- Know when to switch gears.

- Build somewhere you want to work. Many precious anecdotes here about, e.g., organizing a city-wide scavenger hunt for employees.

- Experiences are more effective at motivating employees than and customers than money. This comports with both social science research I’ve read and my own experience. (I have recent experience of this at a company I consulted for, but since it is identifying, I’ll wait until they announce what we did together to go into it. Still: it is amazing how effective turning money into an experience is at motivating people than awarding them the money directly, even though this is crazily irrational. Japanese companies understand this better than anyone: “why pay people so that they can buy objects suggesting social status when you can just award social status directly”, which is the Rosetta Stone for so much of corporate life here it is scary.)

Jason Cohen

I was flagging by this point in the conference and a little terrified about my upcoming speech, so my notes aren’t that great. Jason had a lot of amusing anecdotes from taking Smart Bear code review software from a one-man operation in a small room in Texas through to a sale to another company. (Despite being told, repeatedly, that “Smart Bear” was unprofessional and the name would scare off big Fortune 500s, the company which bought him out later reorganized their portfolio of products under that brand name.)

One amusing story was about Sales Guru Frank. He was a silver-haired slick talker who, for a mere 50% of the equity of the company, promised to sell Smart Bear software to the sorts of huge corporate clients which would bring it from a six figure business to a smashing success. Jason had an absolutely priceless anecdote about how us engineers perceive the sales process: “You know, it’s when you’re in the boardroom drinking some expensive brand of alcohol and you start the conversation with ‘Hey, did you see the game?’ and everybody understands what game you meant and then, suddenly, sales happen.” It turns out that sales is a little more complicated than this (for details, see the Paul Kenny presentation) and, thankfully, Jason avoided getting suckered by Frank.

Similar fun stories abounded but I was too terrified of my upcoming presentation to write them down (d’oh).

The single best takeaway was how to evaluate advice you receive from noted software bloggers.

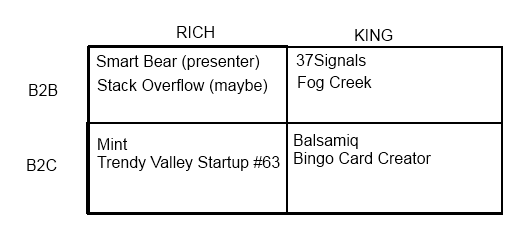

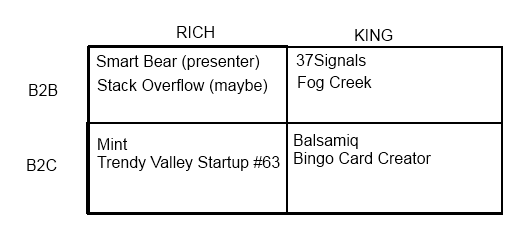

There are two competing motivations for people who start software companies: wanting to maximize one’s financial outcome as quickly as possible (you want to be Rich) and wanting to sculpt the perfect personal niche in which you will be respected and enjoy your day-to-day work (you want to be King). There are two fairly well-known markets for software: B2B (business to business) and B2C (business to customer).

This gives us the traditional four quadrant graph, which Jason decorated with some examples:

The take-away: only listen to advice given from people in the same quadrant as yourself, and you’ll save yourself a lot of pain and cognitive dissonance from getting conflicting advice. (This is overstating the conclusion a wee bit I think, and people change on both axes over time. That said, I’m definitely onboard with “all advice is a product of the circumstances faced by the person giving it”, but I think you can pull lessons from 37Signals in a B2C business or from Joel Spolsky regardless of whether you want to craft the ideal place to work or go big with a VC company or both.)

Sidenote: my business got mentioned from the stage three times, and I’m seriously honored and humbled about being put in that company.

Paul Kenny

Paul talked about the sales function — not just the sales job title — at software companies. See his talk from last year for details about that.

Why do so many salespeople suck? Well, the typical career path requires:

- One year from hiring to get up and running with the particular company/market segment/product.

- One year to achieve momentum in building up one’s list of contacts and starting the sales cycle.

- One year to demonstrably fail to achieve results.

- One year for HR to convert the salesman from non-performing to “no longer with the firm.”

Given that it takes four full years to go through this cycle, you could see a salesman with an impressive resume of 3 ~ 5 year stints at name brand companies with impressive sales to their credit… and not learn, from their resume, that their sales skills are atrocious and their successes were actually the result of products which could be sold solely on the strength of their quality/marketing/brand even with the salesman impeding customer perception of all three. For example, Jason’s Frank probably fit into this category.

Paul nonetheless believes that strictly depending on inbound marketing restricts your business to plucking the low-hanging fruit, and that going solely after low-hanging fruit is not a great business strategy. (This would be an excellent opportunity to whip out the above quadrant map, by the way: if you’re in either of the B2C quadrants, congratulations, low-hanging fruit is your business strategy, and you can be quite successful with it. Ditto 37Signals and many similar cheaper B2B SAAS apps, by the way.)

The point of speaking to customers, which is all sales is, is to reach a mature understanding of what your client values the most. Then, and only then, you offer that to them.

Engineers routinely suck at doing demos for customers because they demo every bit of the interface, from start to finish, going through all the little knobby settings bits. Nobody cares about these things. Demo the bits of the software your customers find interesting. When you email customers, talk about the bits of the software your customers find interesting. When you blog about the software, blog about the bits of the software your customers find interesting. But above all things recognize that your customers find themselves interesting and the software boring unless the software makes a demonstrable improvement in their lives.

Quick tip when speaking to customers: “The most interesting people you will ever meet are the people who are most interested in you.” The average sales rep spends about 47 seconds in talking about customers prior to talking about the solution. That number should be increased, greatly. On the plus side, because the industry is so comprehensively screwed up here, even minor improvements provide an opportunity to surprise and delight customers. “Goodness, the CEO of that company spent five whole minutes talking to me about how we go about our business! They really care!”

(Sidenote: This also goes if you’re selling yourself as an employee to a company. If you’re in an interview and talking about the employer, you are probably going to get hired. For reasons beyond my ken they don’t teach this lesson in college.)

Key takeaway: The quality of your dialogue with customers is directly proportional to the quality of the customers you will acquire. If you understand their needs better, you will close bigger deals with happier customers who consume less resources.

Customer faith in your product as a solution to their problem is directly proportional to how well they believe that you understand their problem. This again counsels spending more time talking to them and asking perceptive questions, then repeating their own language right back at them. If they call it a foo, you call it a foo, even if internally everyone knows it is “really” a bar and, after all, it implements IBarable in the source code. Relatedly, you cannot tell your way into a dialogue with the customer, you can only ask your way in.

Customers have DNA: Drivers, Needs, and Aspirations. You should be capturing your understanding of these as you talk to customers, or you aren’t learning what you need to learn to bring the customer and the firm to a mutually satisfactory relationship.

Some factors to consider

- Customer needs

- Timescale for implementation

- Scalability

- Integration with existing systems/processes

- Affordability

- Results

Customers have many priorities:

- Ego (underrated by engineers in my opinion… even those who own iPhones because they’re worth owning iPhones)

- Perceived gain

- Sense of belonging (“Nobody ever got fired for…”)

- Security

- Ease of use

If you think of a funnel of concerns prior to sale, starting at the top:

- The experiences customers have right now.

- Their business case or project which may benefit from your solution.

- The utility your solution can offer. (Note to engineers: many of you stop inquiring here. That is a mistake.)

- Options they have competing with your solution.

- What the company values in terms of outcomes, drivers, etc.

- Resources they have to solve the problem (i.e. talk budget last, not first)

Founders have an advantage in doing sales, even if they’re engineers who think they can’t do sales. Nobody understands the problem domain like a founder, nobody understands the solution’s capabilities better than a founder, and nobody else can say “You can trust me on this because I build the bloody company” or inspire the same degree of emotional response in a customer that talking to a founder provides. (This is so true in my personal experience. I hear, over and over again, from my customers that they trust me because they know they get an answer “straight from the top” when they send me an email. I hear that most often from people who never emailed me in the first place, or who emailed me with issues that could be easily dealt with by Level 1 CS. This is one compelling reason why I don’t outsource customer service.)

Rob Walling

Rob writes Software By Rob, runs a stable of small software businesses as a one-man show (including, most amusingly to me, selling beach towels — he focuses just on software these days), and wrote a book I really enjoyed. (Flip to the chapter about Virtual Assistants, it is worth the price of the book and then some.) The slides and outline for his talk are online.

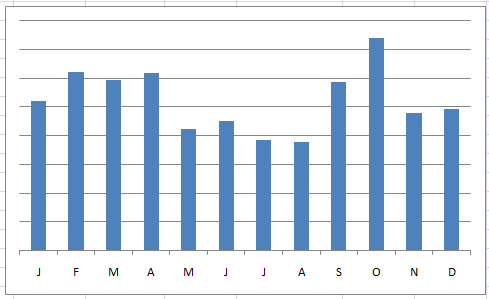

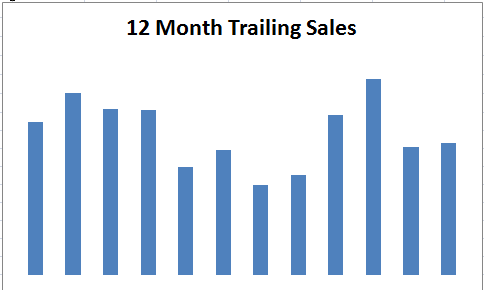

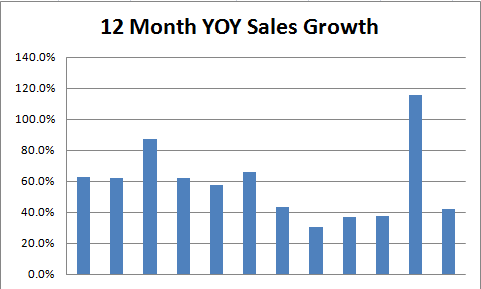

After review of statistics generously donated by several software companies, Rob is of the mind that the most important goal of your website is to bring people back for additional visits, because the conversion rate of your website is much, much higher among engaged visitors than it is among first-time visitors. I didn’t write down the exact numbers, but I recall him citing DotNet Invoice (“written in Ruby on Rails… no, just kidding”), CrazyEgg, and the beach towel site among a few others. Interestingly, a few of the examples had higher average order values for returning visitors, too.

I only investigated this for about 30 seconds, but I have lower conversion rates to the online free trial of my software from returning visitors than first time visitors. That actually isn’t contrary to his thesis, though — it is an artifact of having a very scalable SEO strategy and customer acquisition highly dependent on high-converting organic and AdWords landing pages. This is one of the threats of making decisions based on shallow understanding of what Google Analytics tells you is the “truth” of your business. (One minor surprise: about 60% of my customers who convert from the free trial convert within 3 hours of starting it. Nail that first run experience and nail it hard, guys.)

“The ineffective marketer asks you to buy too soon.” A customer on their first visit could have multiple reasons why they are not currently prepared to buy your software:

- They don’t have enough info about it.

- They don’t trust you. (Oh goodness, this topic is worth a book.)

- They don’t have money to buy it right now. (A particular issue for a $300 invoicing software.)

- The don’t need the software right now.

- They’re never going to buy this.

You can recover from all the issues but #5 if you establish a relationship with them. Permission-based email marketing is the best way to do this, bringing them back to your website via a communication channel everyone has and uses. Repeated, trust-building contact with them will gradually wear down their resistance to parting with their cold-hard cash.

Email is far superior to competing methods of repeatable contact with customers — such as Twitter, blogs, RSS feeds, or your favorite social network — because it allows “personalized broadcasts”, where you can scalably communicate with an arbitrarily high number of people while also making it feel like everyone is getting individualized attention. (Not nearly enough people use this to its maximum potential, particularly with SaaS. Free tip from me: note what search term sent them to your website, put a variation of it in the subject line of the email, watch your open rate go through the freaking roof.)

To get the maximum value out of emailing your customers:

- Have a killer landing page laser targeted on the “give us your email in return for this immediate benefit to you” call to action. Give them a whitepaper or similar resource in return for the email. It greatly, greatly will increase your conversion rate. (Rob is not a fan of free-to-use trials. That is an interesting idea to me, as I come from a “of course the software is free to try out” background. He has achieved truly eyepopping conversion rates to an email submission — 40%+ on some pages. I can’t get that to my free trial, which also requires an email address, and I have pages which are very, very compelling at “selling” that to customers who were looking for exactly what the free trial offers.)

- Give something away in return for the email address. See the slides for specifics, but this has a monumental ROI. (I have some confidential numbers from consulting clients. Suffice it to say this is right on the money.) Interestingly, if you just call a white paper a “report” it has higher perceived value. (News you can use!)

- Set follow-up for emails. MailChimp, my mail provider of choice, calls this an autoresponder sequence. If you take one thing from this presentation, learn and use autoresponders. They will change your email marketing life.

Some excellent tactical suggestions:

- Spam: Don’t spam! Don’t mistakenly get classified as spam by hitting filters. You can pre-test your emails against common filters, like SpamAssassin, to reword against accidental false positives. (A long time ago I worked on anti-spam systems for a living. Oh, the hilarious stories I could tell you. Suffice it to say that a home builder might want to avoid promising that they could “increase the size [of your patio]”.) Incidentally, MailChimp will do this for you for a nominal per-email fee.

- Some words kill open rates if you use them in subject lines. Reminder, Special, % off, and “Help [us]…” are all culprits.

- From Name: your own personal name is best, and role names are a bit worse, company name is a bit worse, and webmaster@example.com is worst of all.

- All advice on emails can be A/B tested!

Peldi (Giacomo Guilizzoni)

Peldi runs Balsamiq, a small software company which has become practically synonymous with low-fidelity mockups for software. He wrote the best blog post on the Internet about seeking coverage for your startup. You should execute on it.

The theme of the talk was worries: worries you shouldn’t have, worries you will have, and what keeps Peldi up at night these days.

Things you should not be worried about:

- Asking customers to pay you money. (Both Peldi and I were shy about this prior to starting, apparently, because we had the genetic flaw all engineers have that says that there might be a bug and, therefore, it is too early to accept appreciable amounts of money for the product. I promise to do my part and say “Charge more” to any person that will listen to me until we have cleansed this from our collective gene pool.)

- Pirates. (Not an issue in practice, you can pretty much fire-and-forget a low-pain DRM system, and since if you’re smart you’re doing web apps anyway this is disappearing from the radar screen entirely.)

- Picking a niche which is too small. (Peldi put up a screenshot of Bingo Card Creator here, to the widespread amusement of the crowd. I later heard more than one attendee say that they were under the impression it was “a funny Italian joke” until I gave my lightning talk. That actually worked out great for my talk’s reception.)

Early worries in the lifecycle of his company:

- When to make the jump from full-time employment to starting your own business. If I recall the talk correctly, Peldi scrimped and saved for a while, sold his shares of Adobe, and emptied his IRA so that he would have a year of runway in hand prior to going full-time on Balsamiq. He also had written code on nights and weekends for several months, so he was not doing a standing start. (And his rise was truly meteoric after that — a combination of product quality and being a marketing genius. If you don’t understand why he is a marketing genius, go back and read that post I cited earlier.)

- Work/life balance. Regrettably, you’re going to have to get your family on board with losing you for a few months while you disappear into the Bat Cave and hammer out your software. (This is my one bone to pick: no, you do not. You can virtually always stretch out your schedule.) Peldi then delivered the best line of the conference: “If you work while they sleep, they won’t know that you’re ignoring them.”

Many people are under the impression that Balsamiq was an instant, overnight success, largely based on Peldi’s embrace of radical transparency and publishing revenue numbers. Peldi had a series of very interesting graphs: the first shows the hockey stick revenue curve that competitors salivate over. Then it zooms out to include the time while the software was getting written (i.e. no sales). Then it zooms out to include his previous career at Macromedia/Adobe where he learned to polish software to perfection in the way that separates Balsamiq from its many, many competitors. Then it zooms out to include his programming career starting at age 12. Overnight success only took thirty years. In a conference with many profound insights, I think this was one of the best ones.

Let me give you an example from my own experience: I recently received a wire transfer from a consulting client, for an amount of money which would be unexceptional to some people and which is staggering for me — more than I’ve ever had accessible in my entire life, by a factor of lots. It was for two weeks of work and was roughly equivalent to what I used to make for six months at my previous day job. The story for how I got to do those two weeks of work starts out with participation on the Joel on Software discussion boards some four and a half years ago. I started dabbling in the topic the work covered almost six years ago. The focus on communication which made it possible to sell the client (and eventually, their team) on the importance of the work getting done can be traced back probably to middle school (when I took up public speaking to get over a speech impediment). You literally needed an entire lifetime to prepare for what you’re doing today.

Back to Peldi: don’t be afraid of an inability to deliver. You’re a talented engineer, you’ll figure it out. If you fall in love with the problem and can discuss it with boundless energy, then every interaction with customers will make your product better. At early stages in the product lifecycle, feedback from customers is a much better thing to capture than mere money. (Peldi gave away licenses like they were candy during the first few years. Again, read the above blog post, in addition to getting great feedback this was a great PR and linkbuilding hook.)

Peldi had an extended discussion of how you can use Obama’s debate script as a model for addressing your fear of confrontation with customers. While I’m not a fan of his politics, I agree, he is an excellent communicator. There was a flow-chart involved, but the core is:

- Thank the customer for taking time out of their busy life to communicate with you.

- Empathize with them.

- Apologize if they’re ticked off, even if they have no right to be. (Oh, crikey, how much do I agree with this.)

Lightning Talks

All of the Lightning Talks were delivered by non-professional speakers. They followed a murderously difficult format: you get 15 slides which get auto-advanced every thirty seconds, and that’s it. You might think that means you can get away with slapping together something in an hour: oh no. In discussions with my fellow lightning talkers, we agreed that there has been something of a “lightning talk arms race”: the two talks I was most impressed by took over 24 hours to prepare, and mine took at least twelve solid hours over two months, with probably half of that being rehearsal until I could literally count out thirty seconds with a prepared spiel delivered in a voice other than my own.

I’m going to refrain from talking about my own lightning talk. Why? First, it relies on a “reveal” for a great deal of the impact. Second, it was, far and away, the best speech I’ve ever given (out of thousands — some people play sports, I did public speaking). The combination of heartstopping terror and the crowd reaction produced a strange alchemy which made the talk as delivered a lot better than the videos I made of myself performing it in a room for my webcam.

I’m told it was recorded and the video will be made available to the public. I’ll tell you when it is ready. I promise you, you’ll enjoy that a lot more than you’ll enjoy me posting the slides and a video of me saying virtually the same words to a wall.

As to the lightning talks other than mine, a combination of heartstopping terror about my talk and the exigencies of the format mean that my notes on them are woefully inadequate. I expect that a few of the lightning talks will eventually be put online at some point. Those videos will do them better justice than my hazy recollections, so I recommend waiting and seeing them.

Eric Sink

Eric presented the nuts and bolts of what happens if your company (or, in his case, a product thereof) gets acquired by BigCo (in this case, Microsoft). Short version: a lot of pain and suffering, followed by a check so large that the VP of his community bank said putting it in his account would throw their company into absolute havoc because of the impossibility of putting so much money to work. Let me emphasize the pain and suffering part, though. (The low point: when the deal had consumed his waking life so much that Eric was reduced to taking a phone call from his lawyer while in church.)

One of the weirder points for Eric was that, with a cast of literally dozens working the Microsoft side of the deal, he never met or learned the identity of the person who actually made the decision to buy the product. In a gang of people with confusingly similar job titles and descriptions, it seemed that “nobody was in charge.” The deal was lead by a particular point of contact — we’ll call him Fred — who, as a trained negotiator whose full-time job is assimilating biological and technological distinctiveness, was a thousand times more prepared than any entrepreneur will ever be.

The process involves a long rigmarole of procedural steps. You’ll want to see the full talk for the breakdown, because I’m hazy on it, but it involved multiple levels of due diligence, getting signed agreements covering IP rights from every person who had ever put a finger to a keyboard within a meter of the source code (cough start work on this today if you want to sell cough), etc etc.

While many entrepreneurs obsess about The Number, what you actually get is The Deal, which ended up being 150 pages of bullet points all individually negotiated covering every aspect of the transfer. This included guarantees of treatment for employees who were relocating with their product from central Illinois to Microsoft, all manner of indemnifications, tax treatment of the deal, escrow (code and otherwise), the exact structure of compensation for the deal, the terms of the NDA covering material terms of the deal, etc etc.

The deal nearly fell through at several points, over contentious negotiating issues. Nearly might not be strong enough: it was dead. The deal was off, and the other side went to total radio silence for a period of weeks. This was necessary to get the best achievable outcome for Eric and the team. Eric is of the opinion that you need to walk away about twice: less and you’re getting screwed, more and you’re buying more heart attacks than the marginal improvement in terms is worth. (One friend of his — in the elite fraternity of “people who have sold a company”, whose stories “you only become privy to after you have joined the club” — had to walk away five times.)

One interesting point raised in discussion was the importance of having multiple interested buyers so that you can play them against each other. (Michael Pryor from Fog Creek is especially articulate about this one. The short version: if your BATNA is “get bought by the other guy”, you have more leverage than if your BATNA is “you don’t get acquired, six months of work flushes down the drain, and the company potentially withers.” The long version: ask Michael.)

Dan Bricklin

So here is a generation gap question for you: I didn’t know who Dan Bricklin was, and someone said “Well, duh, he’s the guy who wrote VisiCalc.” I then had to Wikipedia VisiCalc because I had never heard of it. For those of us who were born in the eighties or later: he invented spreadsheet software. Yowza.

In addition to a hundred and one precious anecdotes about inventing spreadsheet software while a poor grad student (my favorite: the development machine and sole source repository, which cost the team’s life savings, being protected from a plumbing problem by constant vigilance with mops), there were a couple of generally useful takeaways:

- Customers have jobs that they need to get done. Identify those jobs. Build general purpose software which allows them to get the jobs done.

- The perceived value of general purpose software, which solves a variety of current and anticipated needs of a customer, is higher than that of software which solves one specific pain point. (I respectfully disagree, but then again, I didn’t invent the spreadsheet.)

- Software which the customer can customize to their particular needs allows “tailoring at the ends.”

- The two-week payback rule: software sells itself if you can reliably demonstrate that your product will recoup the purchase price within two weeks. VisiCalc (spreadsheet on a mini-computer) was so disruptively better than using a time-sharing system to do calculations that you could buy the software and the system to run it for just half of one month’s metered use of the big mainframe you leased time on to run your TPS reports. That contributed to it selling 700,000 copies, back when distribution channels for software were stone age compared to the alternatives we have today. (My unconscious brain was virtually screaming: “You can sell software without a website?!” when I saw the magazine ad slides.)

- Games and relative cheapness were very important in driving new technology adoption. Note that this, and the “general purpose applications win” rule, are demonstrated in abundance by the runaway success of the iPhone.

Derek Sivers

Derek had originally planned on delivering a talk about various profit models for software companies (spiritually similar to this talk). I met him for the first time at a speaker’s dinner. During the course of dinner, one topic frequently returned to was why we do what we do. Derek told a very moving story about how he sold CDBaby, his labor of love for many years, and someone (I think it was Rob Walling) suggested that he do that as a talk instead. He ended up doing so.

Where to start:

Derek originally got into CDBaby to sell CDs of his own band’s songs. Back at the dawn of the Internet, getting a merchant account for selling CDs was a multi-month process, with plenty of administrative hassle and pain involved. Derek persevered and, with no programming background, managed to hack together enough CGI scripts to get a buy now button on his website in a mere three months. (And again I bless my lucky stars that I had Paypal and e-junkie.)

After he started selling CDs, some of his friends with bands said “Hey man, that’s really cool. Can you sell my CDs, too?” So he’d hack the scripts again and then he was selling another CD. Eventually, word of mouth had gotten to the point where his band’s website was colonized by other bands who lacked a good way to sell their CDs online, and CDBaby was born. His blog covers this story in detail.

Derek was once interviewed by NPR and, when asked about his exit plan, said that long after the sun had set on CDs and when he was old and grey, he’d still be shipping CDs to the last aging person who swore that the CDs they played when he was young were far superior to that newfangled hologram 7D garbage that passed for music in 2050.

This turned out not to be the case: after a major rewrite of the CDBaby source code, where Derek achieved pretty much every technical goal he had for the site (and had paid back years of code debt), and after changing his management style such that he became totally superfluous in day-to-day operation of the company, Derek became an absentee owner of the company he founded. Some people might view that as a wonderful outcome. It turns out that Derek’s employees viscerally hated him for it: convinced that they were the true bearers of the CDBaby vision, rather than the unseen owner who many of them had never even met, they began organizing what could be described as a corporate coup.

When Derek found out about this (oh, the joys of reviewing MP3 recordings of meetings at midnight), he realized that he was well past the point of no return with regards to employee loyalty. So he turned Apache off and started composing an emailed pink slip for the entire staff. No, really. Luckily for all concerned, he eventually decided to sleep on it, and came back to advice he had received from Seth Godin: if you are no longer passionate about the problem, you owe it to your customers to sell to someone who is. Apache went back on and the email was not sent.

Derek pursued a few options for getting rid of the company. One was to simply give it away: he actually pursued pulling off a Willy Wonka and putting five golden tickets in CDs delivered by his company, with the five holders invited to present their visions for the future growth of the company, and the winner (as decided by a vote of customer musicians) receiving the entire company. Due to fortunate advice from friends regarding the desirability of being sixty and having no money, Derek threw away the golden tickets he had gotten printed and decided to do the more usual thing and just sell.

The sale came with a wrinkle: Derek first transferred the company into a charitable trust, then sold it, meaning that he is forced to draw 5% of the sale price per year, and when he passes away the principal and investment gains (if any) of the trust will be distributed to the charitable causes of his choice. Derek claims this is mostly not for altruistic purposes: he asked his lawyer how to achieve “I want to have a stable income until I die, and that is all I need”, and the charitable trust was an attractive option.

Derek mentioned that having competing bidders was wonderful, since they could be played against each other. This helped him achieve some goals he had in selling the company:

- I’m out. (Founder participation as a consultant or employee for a defined term is a frequent requirement of sales. Derek took that option off the table entirely as a precondition of sale.)

- I keep my database. (A decade of running essentially a marketplace between music sellers and music buyers gives Derek a powerful foundation for future endeavors aimed at helping musicians, his perennial concern.)

- I keep helping musicians. (The non-compete was narrowly tailored so that he would not sell CDs again, but could continue participating in the music industry. Sometimes non-competes are are very broadly drafted — I’ve heard possibly apocryphal reports from one that, boiled to its essence, barred a technical founder from programming for the duration that a large company with a small-sounding name continued selling operating systems.)

Joel Spolsky

I’m pretty sure most people know Joel co-founded Fog Creek and Stack Overflow.

Continuing the theme of the later part of the conference about big picture questions like “Why?”, Joel’s presentation was probably the bravest speech I’ve ever heard. Theoretically, it was about the story of transitioning from a low-growth (ish) software business like Fog Creek to a high-growth VC-funded shoot-the-moon attempt like StackOverflow. However, it dwelled on some intensely personal questions about leadership, philosophy, and intra-team conflict, and I don’t know if I could have discussed them at that level in public.

Let’s see: the brief takeaway on seeking investment is that if you’ve got a successful track record as a well-known CEO and a good idea which also has demonstrable traction, raising capital is fairly easy (Joel and company were practically booked solid when they went to Silicon Valley to meet with VCs). However, it still has some of the industry seediness. One VC who they met with, who ended up not investing in the company despite early promise, later tried his darndest to cause a rift between Joel and his co-founder (Jeff Atwood) so that he could pick up the pieces. Another VC was quite interested in StackOverflow, provided it was CEOed by anyone other than Joel.

Interference from VCs aside, they eventually got signed by Union Square Ventures, who have treated Joel and company fairly. The cultural gap between a self-funded software company and the VC world has caused a few disconnects (for example, at one point they found that StackOverflow had $200,000 lying around that they had forgotten to disclose based on revenue, and they asked what corporate structure should receive it or whether they could licitly award it to employees: the VCs were totally uninterested in $200,000, and rather amused at the notion that a company they had funded could actually have had a profit from operations at the stage they were at).

StackOverflow has a very different corporate culture than Fog Creek, which Joel describes as a software company founded with the goal of becoming an “intentional community” whose mission in life was providing programmers a great place to work. It was explicitly analogized to a kibbutz, with collective ownership, the profit being redistributed among employees, and decisions specifically made to promote community (one which stuck with me was the huge importance placed on breaking bread together on a daily basis).

The culture involves decision-making by consensus. For a variety of reasons, StackOverflow does not operate in this fashion. This lead to some contentious battles between Joel and Jeff, exacerbated by the aforementioned evil VC, who tried to split the founders to pick up the company on the cheap. Among other things, After frequent screaming and crying, Joel figured that his traditional style of hiring smart people and letting them get things done wasn’t working, and he called in a CEO coach for assistance. He thought he’d get management advice on how to better run meetings and write org charts and do the things that CEOs do.

Instead, he got corporate psychoanalysis, and was introduced to the notion that the CEO’s job is not to manage the company, but to lead it. This was particularly important as he was CEOing two companies simultaneously. Once he started accepting that “I am the CEO, I have heard your viewpoints, we do it my way and that is final” was also a valid managerial style, conflict in the team ironically decreased greatly.

On the question of why we do what we do: Fog Creek is the company Joel designed to have a great place to work. StackOverflow, on the other hand, is targeted at contributing one significant thing to the world: fixing the broken style of asking expert questions on the Internet. They want to bring the improvement StackOverflow brought to programmers to the wider community (and communities) of interest who Google questions which have canonical good answers and find a SERP stuffed with 10 year old VBulletin threads where the answer is on page 7 in between a cat photo, a flame war, and the announcement of the forum’s guru’s goddaughter’s wedding.

Joel would prefer to work at Fog Creek, but thinks he has an ethical responsibility to make StackOverflow succeed first, because — irrespective of Fog Creek maximizing his personal enjoyment — StackOverflow has the potential to contribute a large social good to the world at large, and he views this as ethically mandatory given the opportunity. He contrasts this to the 37Signals-esque notion of being content to run a small business because it allows you financial success and the lifestyle you enjoy (although he was quick to note that, while saying this, 37Signals gave the world Rails and teaching, so their own ethical bases are covered).

For an example, see CraigsList, which has moved a huge amount of wealth from newspapers to the posters of classified advertisements by making classifieds free. CraigsList is run with a goal other than profit, and would instantly be a gigantic company if they charged for ads in categories other than the ones they do now (which they do as a spam-control device). Joel argues that Craig should do this, because the massive wealth transfer his business enabled has redistributed the producer surplus from newspapers (which once used it for a socially beneficial purpose: underwriting unprofitable but socially beneficial local investigative journalism) to a consumer surplus for “people selling couches, landlords, and pimps.” His point was that, when we know the trade-off our businesses are making, we have an obligation to choose the results wisely.

I am perhaps not doing this point justice: the two minute thumbnail sketch of the argument I heard Joel deliver profoundly altered my perception of where my company fits into the larger tapestry of my life. I would previously have characterized, e.g., the decision to keep the company small as being essentially a personal aesthetic choice with no moral consequences, akin to picking colors for one’s bedroom. I will be digesting the implications of this for a while, but I think I am now convinced that that is probably untrue.

A sidenote: since, pace Seth Godin, the cost of producing software is cratering and the competition is exploding, Joel is gradually coming to the belief that the value in a software company isn’t the code, it is the community. The thing StackOverflow had to offer VCs wasn’t the code (which, to quote what has become an in-joke among HN readers, “could be written in a weekend”), it was the “large number of engaged users.” Microsoft estimates there are 9 million programmers in the world. StackOverflow has upwards of 8 million monthly uniques. They’ve become the canonical go-to place for answers in the programming niche, and have dreams of becoming the canonical go-to place for answers for all expert queries which have canonical right answers, from tax advice to math theorems to gardening and many points beyond.

Commitment To Community & Disclaimer

(Back to top.)

Like I mentioned earlier, I strongly recommend you attend Business of Software. Even at close to 10,000 words, this post captures a bare fraction of the value I got out of going to the conference. I understand that both the ticket and the ancillary costs of attending are quite high for bootstrapped startups. Trust me on this one: a plane ticket from Japan to Boston and four days in a hotel wipe out nearly a month of revenue for me — and it was worth every penny and then some.

Neil Davidson, the conference organizer, was very generous with giving away tickets to the event to deserving bootstrappers. In the spirit of the overwhelming generosity of the community and the thoughts sparked by talk of our ethical responsibilities, I will likewise make an opportunity for at least one marginal person to go next year. Watch this space — I’ll hammer out specifics closer to the actual event.

Now, the obligatory disclaimer: have never accepted advertising on my blog and don’t feel like starting anytime soon. I was given a free ticket to the conference in return for presenting my Lightning Talk at it, and after winning the competition for best Lightning Talk (which I literally did not know existed until five minutes before it was announced that I won it), I received a Kindle and an invitation to a very nice dinner. I’m easy to impress, but not that easy: my effusive enthusiasm for this conference comes from it being one of the highlights of my professional career, not because of compensation.

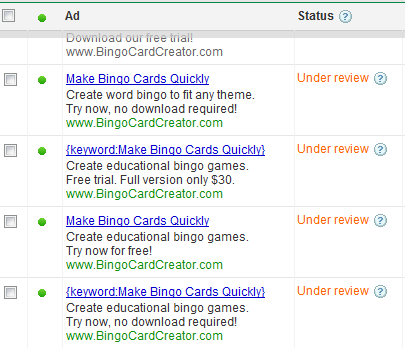

After filling in everything, I hit Submit expecting to be taken to a page which had an “OK, now actually tell us what the problem” comment box was. No need — it has been optimized away! Google doesn’t even want that much interaction. (The last time I went through this — sometime last year — I recall there being a freeform field, limited to 512 characters or so. I always use it to explain that I am not a gambling operation and if they want confirmation they can read the AdWords case study about my business.)

After filling in everything, I hit Submit expecting to be taken to a page which had an “OK, now actually tell us what the problem” comment box was. No need — it has been optimized away! Google doesn’t even want that much interaction. (The last time I went through this — sometime last year — I recall there being a freeform field, limited to 512 characters or so. I always use it to explain that I am not a gambling operation and if they want confirmation they can read the AdWords case study about my business.)

Recent Comments