Executive summary for your CTO: If your company runs Rails 2.3 apps, switch to Rails LTS, a commercially supported fork of Rails. If you do not do this, and do not take one of the more elaborate mitigation steps as described below, your Rails applications will be compromised, you will lose the servers you run on, and your business will suffer substantial losses.

Two of my businesses run on top of Rails 2.3.X, because they were started when that was the best option for writing production software on Rails. This is true of many, many commercial Rails applications (loosely defined as “ones which make money for businesses”), both ones which are used only internally and ones which are public-facing, like SaaS sold on the typical pay-for-it-monthly plan.

Rails 2.3.X is, with the release of Rails 4, currently unsupported. What does that mean? It means that the Rails Core team has washed their hands of dealing with security problems on the platform. This means that if, for example, Rails had another bug or series of bugs like the string of Severity: Apocalyptic vulnerabilities disclosed in January, individual users would be responsible for arranging for their own response rather than just waiting for a new release and bumping their gem version.

Why Is Anyone Still on Rails 2.3.X?

I know many folks in the Rails community wonder why anybody could still be using a years-old system. Suffice it to say that Rails 2.3.X remains a productive, viable way to develop applications. Some sites which are under active development daily still run on 2.3 — Github, as one prominent example, runs on an internal fork. (More on them later.) They’re one of a dozen prominent companies I could name with the main application still on 2.3. Other companies have software which is more or less done running on 2.3 — for example, many companies run internal HR, accounts receivables, CMSes, etc which were written by boutique Rails consultancies back in 2010 and haven’t been upgraded because HR hasn’t really changed all that much. Some companies even run across multiple versions of Rails, where the main app might be running on a fairly recent version but the supporting cast of web services, admin dashboards, and internal company tools are at whatever version they were at when they were created.

Much love to Rails Core for continuing to push the state of the art in web development forward, but not every app needs to be on that bus. Bingo Card Creator, for example, still has several hundred thousand dollars of commercial viability left in it, but Bingo Card Creator is done. It has achieved everything it ever wants to do in terms of bringing bingo cards into an AJAX-y web application, and doesn’t have any possible upside for moving to the new hotness. That said, it still needs to avoid losing users’ passwords/credit cards to hackers, and it can’t host a botnet within my firewall. That would be, ahem, problematic.

[An aside: Let me sketch out “problematic” a bit: Appointment Reminder — also on 2.3.X — has patient information from several large hospitals in it. Leaking this information would be, obviously, severely negative for my customers, their patients, and my business. In addition, I’d be subject to fines which scale to how many bytes of information I have control over… yeah, ouch, I know. I’m insured against that risk, but if I tell my insurance company “Health and Human Services wants $600,000 from me. I guess you just lost your bet with me that I’d be competent enough to secure my server eh?” one of the first questions they’re going to ask is “Did you actually take those security measures you promised you take, like say using all commercially reasonable means to maintain patches on your applications?”, and if I answered in the negative they’d say “Wonderful, this loss isn’t covered under the policy you bought. Hope you have $600,000 lying around. Thanks for your business.” Data security is serious business for many people.]

The Rails Core Team Is Not At Present Interested In Supporting 2.3.X Going Forward

A few people, including myself, have told Rails Core that their businesses use 2.3 apps and that continued support for 2.3 would be a major win for them. Rails Core is uninterested in supporting 2.3 going forward. To be totally clear on this point: that’s fine. Rails is an OSS project which implicitly requires a $X million budget a year in employee salaries to continue running, and those salaries are overwhelmingly paid by for-profit companies. Those companies graciously allow their employees to contribute their time and IP back to the community. If 2.3 support isn’t a priority for Rails Core and/or their employers, then obviously they’re free to take the project in directions which are.

One reason why 2.3 support is not a priority is that, as every maintenance programmer knows, supporting old software involves a lot of boring scutwork. Rails Core felt there wasn’t a manpower or monetary budget for underwriting this scutwork. Some people expressed the opinion that folks asking for 2.3 support were freeloaders who were prepared to contribute neither patches nor money towards the effort. That’s a prediction that, in many cases, I would have had a lot of sympathy for. It’s very easy to criticize people who actually do things for a living on Github/Twitter/etc. To head this off, when I made feelers about maintaining 2.3 support, I made it explicit that my company would cut a $10,000 check to make it happen. (Kalzumeus Software is, to put it mildly, not nearly where most of the money is being made in Rails 2.3 apps, but $10,000 is trivially affordable at even our microscopic scales, and I thought this would demonstrate that The Enterprise (TM) would be able to fund this effort, in much the same way that The Enterprise (TM) spends billions of dollars a year on software maintenance.)

I was told, informally, that that was a nice gesture but it wouldn’t sway minds. So I started looking at other options.

Your Options If You Are Currently On Rails 2.3.X

1) Do nothing and, with probability of 100%, get your server owned.

Have I beaten this drum enough? Thump thump thump. If any server operated by your company is on an unpatched version of 2.3, that server will be compromised by the adversary. Every Rails 2.3 application is, as of today, unpatched. (Did you backport the fixes for e.g. the translate helper method XSS bug? No? Then you’re running unpatched. That bug is actually from 2011. The ones from Q3 2013 are going to be much more interesting.) You cannot afford to remain like this. You will wake up one day wondering “Why is my web server trying to download and run a rootkit?” … well, if you’re lucky enough to detect it prior to being rooted. Since covering this subject in depth in January I have heard harrowing tales of, e.g., CTOs at well-regarded companies who will not allow engineers to upgrade from vulnerable versions of Rails because they’re afraid the patched versions will cause regressions in their applications. That will be a very interesting excuse to trot out to management or the board when asked why you lost 100,000 credit cards or why your entire network has joined a botnet.

2) Rewrite your applications for Rails 3 or Rails 4, which are currently supported.

You can upgrade an application from Rails 2.3 to Rails 3. Upgrading point releases is (aspirationally) a fairly painless experience on Rails, but the Rails 2 to Rails 3 transition is a serious engineering project for non-trivial applications. A short list of issues:

- Many of the gems/plugins which you might be using with your current application will not be compatible with Rails 3. You will either have to upgrade them, find a (hopefully compatible) fork for Rails 3/4, or fork them yourself and +1 the number of old projects you’re maintaining. Some gems/plugins which have variants which are compatible with Rails 3 have had breaking API or behavioral changes in the interim.

- Rails 3 made a really good decision to enable HTML escaping by default, for preventing XSS attacks. If you’re coming to this from an old application, you are likely going to have to dig in and either root out or mark harmless every time your views/helpers/model objects/etc return HTML when you expect them to. That can be an involved project.

- Most Rails projects of non-trivial size will play with the Rails internals, via calling private methods or monkeypatching core behavior. For example, Bingo Card Creator takes over the standard way of locating layouts to support more extensive A/B tests. Since the internal structure of Rails changed dramatically when it absorbed Merb, you’re going to have to rewrite that sort of code from scratch. (If you’re watching from the sidelines, you might think this is inherently a dangerous practice, but be that as it may it is virtually universal in the community.)

- You might decide to switch from Ruby 1.8 to Ruby 1.9, depending on how quickly you jump up the Rails version ladder. That will make it a very, very painful transition for you, because the standard library API has breaking changes and the language syntax itself has breaking changes. There are also non-breaking changes where the behavior of code will just change overnight — e.g. Date.parse(“5/6/2013″) can be May 6th or June 5th depending on what version of Ruby you are running. And the encoding issues. Oh God.

My ballpark estimate for upgrading Bingo Card Creator to Rails 3, assuming market rates for Rails contractors, is approximately $20,000. It is substantially higher for Appointment Reminder. Neither of those applications even approach the complexity of some of the commercial Rails 2 applications. It’s easy to imagine many companies spending six figures or more on the upgrade. (If this is difficult for you to imagine, consider that the fully-loaded monthly cost of a full-time intermediate Rails programmer is approximately $20,000 in some localities, so if you use more than 5 man-months, there you go. There are many, many companies for which that would be not nearly enough to complete the upgrade.)

This assumes that your application is in a happy place to begin upgrading today — for example, it has been well-maintained, has very good test coverage, and you have the original programmers on staff. Unfortunately, many applications in maintenance mode are not in this position. They might have been ordered back in 2010 for $40,000 from a boutique consultancy that no longer exists, for example. That doesn’t inhibit a company’s day-to-day use of the application in 2013, because CRUD apps don’t suddenly stop working even if the original programmer dies, but would substantially complicate a very in-depth maintenance project.

3) Support Rails 2.3 yourself

You can, of course, fork the Rails 2.3 code and improve on it yourself, including by developing and incorporating security patches. Github took it upon themselves to do this, for example. It’s viable if you have a team of very capable programmers and the bandwidth to drop everything you are doing at 3 AM in the morning and address new Rails vulnerabilities. (Again, if you don’t do that, your server gets owned.)

This option is not for the faint of heart. Some parts of the Rails framework are very ambitious engineering — take ActiveRecord, for example. As is true with most software projects, even the people who wrote it the first time don’t fully understand what it is doing. You get to start working on rebuilding their undocumented organic knowledge now, and doing security patches later. You might think that you have a helpful ally in the test suite but it is not actually deterministic, because many of the tests rely on things like e.g. the ordering of keys in a hash, and this is not guaranteed on Ruby 1.8.

If you’re Github or another large consumer of Rails, you might be able to guarantee sufficient availability of competent, security-focused programmers such that you can both proactively find vulnerabilities in Rails 2.3 and reactively patch announced vulnerabilities before your app servers join their friendly neighborhood botnet. This is not viable for all companies which use Rails 2.3 in a commercial fashion — for example, if you’re an insurance company which has a line-of-business Rails application, it is highly unlikely that you have the engineering bandwidth to do this. My company has the equivalent of 0.2 full-time intermediate programmers working for it, and if I were to keep on top of Rails security, I’d probably have no time for improving my applications or for writing code to support marketing/sales goals.

4) Pray that someone supports Rails 2.3 for you

Rails Core obviously aren’t the whole of the Rails community. It is possible that somebody else will take up the challenge of supporting Rails 2.3. For example, Github has their fork, as mentioned. It is possible that you can just sit downstream of that fork and have things work for you. I know a few people who are implicitly dependent on the Github fork, for example.

Why didn’t I go down that route?

- Github’s fork currently supports Github’s needs, but it isn’t a formal commitment to the community or anything. They could drop it at any time, without notice. (I might be outside the loop, but I don’t even remember it being announced as existing.) This makes it difficult to rely upon for consequential business decisions, like “Can I afford to commit all weeks in October 2013 to other projects or do I need to keep something in reserve for a panic-upgrade from github/rails to whatever my next best option is then?”

- As an informal project, there is no release process for Github Rails. You’ll have to build your own gems for it, on your own schedule, without guidance as to where known-good commits are on their work-in-progress branch. This could be problematic if you slurped down a security patch and got Github-specific code which, e.g., broke Ruby 1.8 compatibility (check their commit history).

- Github’s fork of Rails 2.3 is, to my cursory view, not designed to be exactly compatible with 2.3 as used by places other than Github. It is an extraction from their working system. I can’t be sure that moving my systems to Github Rails isn’t going to cause them to break in all sorts of fun and subtle ways. (For example, see this commit, which rips out the default YAML processor. That is, in isolation, a decision that I’m totally on-board with and am reasonably sure won’t break my app. One commit down, 53 more to audit.)

- I don’t think “I had no formal relationship with Github but decided to rely on them because they’re good people” is an answer that lawyers at Health and Human Services or my insurance company would tolerate as a commercially reasonable business practice, in the event that a compromise of my site eventually happens.

5) Pay for a commercial fork of Rails 2.3

So after looking through the other options, and getting turned down by Rails Core on my attempt to essentially buy support for Rails 2.3 from them, I started looking for other people to take my money. It turns out that there is a consultancy in Germany called Makandra which maintains an internal fork of Rails, because they have ongoing support obligations for 50ish applications currently in commercial use by their customers. They also have a team of a dozen Rails experts. This puts them in a pretty good position vis-a-vis new security issues: they’re already committed to fixing them quickly (since they have 50 apps depending on it), and they have sufficient engineers to be able to do that.

So I made them a proposition: If they cleaned up their fork such that it could be consumed outside their company, and contractually promised to maintain that fork against newly discovered vulnerabilities in Rails, I would be willing to pay them a substantial amount of money for that. This frees me from having to do it myself, and I have high confidence that “We engaged a firm of engineering experts to handle that aspect” will pass muster with customers, regulators, and my insurance company. This is similar to the Long Term Support option that you could buy from e.g. RedHat if you didn’t want to be on the latest version of their distribution. The name of the fork is, appropriately, Rails LTS. You can buy access to it and use it in production today.

It seemed like a bit of a waste for this relationship to only benefit our companies, given that Rails is OSS and we both continue to benefit from the community, so we hashed out a way to make it work well for everybody. Makandra has substantial ongoing engineering expenses in doing the scutwork that Rails Core correctly observed the community is unwilling to do, and it cost them even more to get it into a state where it was releasable for consumption outside the company. Accordingly, “I’ll just pay you to do that, and you OSS the code” wasn’t going to work for them.

So we split the difference: we agreed that I would be Customer Zero for Rails LTS, guaranteeing that it was commercially viable for them to do the engineering work necessary to release it. They will sell it to anybody, for very, very reasonable rates relative to the amount of money Enterprise software companies usually charge for commercial support agreements. If you buy it, you get support integrating it into your application and, more importantly, guarantees with regards to timelines for them to address new issues. This means that you can sleep soundly know that it is someone’s contractual obligation to drop everything and address any Priority: The World Is Burning vulnerabilities which get discovered in August.

Normally, when two enterprises get into a support contract with each other, the community doesn’t explicitly benefit. I wasn’t thrilled with that notion, so after some negotiation we agreed on a model which preserves Makandra’s interests but also benefits from the community: all code produced under this arrangement is OSSed under the MIT license (the Rails standard) 10 days after being produced. This means that if you need it to keep a commercial service up and running, that is something you can buy, but if you have a hobby project and are OK with a 10-day window for possible exploitation, you can just slurp down patches from their Github account as they become available. Nothing the community currently has gets taken away as a result of this arrangement: you can still choose to use the Rails Core version of 2.3 on your own recognizance (and get no security patches), or you can buy Rails LTS (and get new patches written in a guaranteed timeframe for new issues), or you can use the community version of Rails LTS (which did not exist but for me bankrolling it) and get your security patches taken care of for free.

The community patches are, naturally, available for Rails Core to backport if they would like to do so. I approached them about doing that, and they say it is a possibility if Rails LTS turns out to be a sustainable thing. That was prior to it being funded and released.

You Might Have An Objection To This. I’d Like To Preemptively Answer It.

“But Patrick, switching to a fork is hard!”

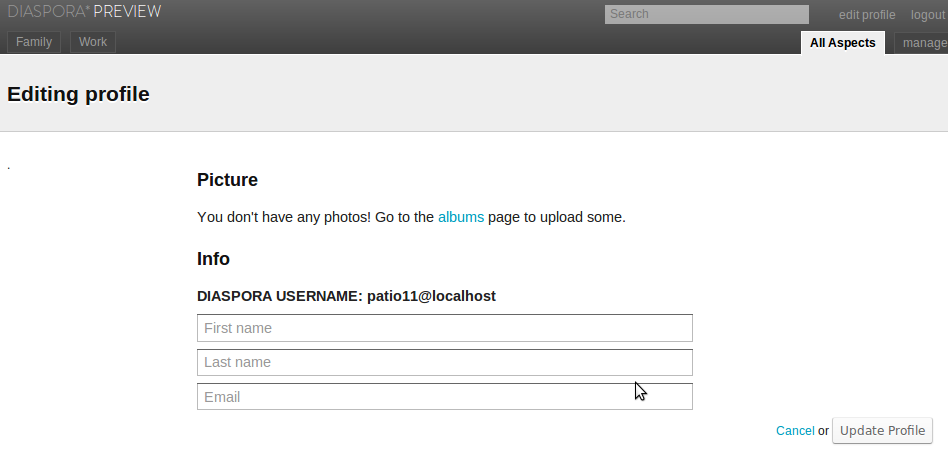

One of the core design goals of Rails LTS was making sure that you can upgrade to it without requiring that you modify your app. If your Rails app uses Bundler, it’s as simple as changing a line in your Gemfile and running “bundle update”, then redeploying. If you don’t use Bundler, you can build the gems locally and then deploy them as per these instructions. I tried doing that for Bingo Card Creator, which didn’t use Bundler, but it turned out to be faster to just migrate to Bundler. (If you have a 2.3 app that hasn’t done that yet, instructions for switching are here. This took approximately 45 minutes for me, mostly as a result of not having a clear all-in-one-place view of my app’s dependencies.)

Since Rails LTS is exactly the current version of Rails plus security patches and tests (diff them if you don’t believe me), it is highly unlikely to cause problems for your application. They’ve promised that featurewise it is frozen in amber and, unless a security issue necessitates it, the API will not change as a result of security releases. (This is a policy whose adoption would be widely beneficial in the Rails community. cough) Both of my applications worked with flying colors. There’s an optional “hardened mode” you can activate (one line in your environment file) to disable some features of Rails which are often unused and have recently been demonstrated problematic, like the “Rails can take XML requests and create objects from them then insert them directly into the params hash, including perhaps deserializing embedded YAML in the XML, which can result in arbitrary code execution” (a feature which, to put it mildly, is not required by much of the community).

“Can we trust this to actually, you know, work?”

Great question. They’re sufficiently credible to me that I cut them a check for $10,000 and have essentially delegated to them a portion of the application security burden for my business, which is a bet-the-business issue for me if I can’t get it right. They have a strong record of bringing client projects in, including ones which are technically ambitious. They have a demonstrated commitment to open source and to Rails 2.3’s ongoing viability as a platform. I think that’s the best testimonial I can give them, but feel free to spend a few hours spelunking in their code if you want to feel more secure about making the decision. (If you want to look at the Rails LTS code in particular, can I draw your attention to the now-actually-working test suite which newly includes tests for the security patches released this year?)

“Why would we pay money for OSS code?”

You’re not really paying money for OSS code which already exists, you’re buying the guarantee that new code gets written at non-deterministic times in the future before the lack of it causes an emergency for your business. It’s closer to an insurance policy than it is to source code.

You’d pay money for this for the same reason you pay engineer salaries: because the code provides business value to you. If you’re a CTO, you should understand that there is definite value in not having to bring your applications down because their servers have been rooted. You should also understand that drop-everything-hair-on-fire vulnerability resolution is not something your engineers are particularly good at and not something which you want periodically disrupting them from shipping applications to your paying customers. You can either pay your engineers to continue monitoring and patching Rails for you, or you can buy Rails LTS. Your call. Their entry-level plan costs ~$200 a month, which is approximately the cost of one or two engineer-hours. (Are you a Rails dev? If you think you’re capable of identifying and fixing Rails framework issues and you don’t charge that much, raise your rates. Are you a CTO? If you think your engineers are capable of this and they don’t charge that much, prohibit them from emailing me, so that I don’t introduce them to more rational firms.)

If you don’t have $200 in the budget, and you at a real business, you either need a) a reality check about your business or b) a heart-to-heart discussion about what will happen when your servers join a botnet. If you’re running a hobby project or are still in the first few weeks of running your business, then you should switch to the community version of Rails LTS, which is a substantial improvement to your security at no monetary cost. Or you can just wait until your server gets owned, because that reliably makes people discover budget for security. (It also could very well result in firings, so I wouldn’t rush to this option.)

“The Rails LTS plans are too expensive! I would pay for this but only if it cost, like, $5 a month!”

Horsepuckey. The hypothetical person saying this is a textbook pathological customer: they’re both deeply irrational (if the app’s security was worth $5 a month then the right answer is probably to shut it off and save the server cost) and likely to be far, far, far too much headache for professional Rails engineers to have to deal with. I’m glad their mail is not going to be in the same inbox as mine when I ask questions about new security issues.

“I could totally duplicate all that work for free! And I’m going to do that! Nyaa nyaa!”

In the immortal words of OSS passive-aggressivity, patches welcome. It would be an awesome thing for everybody if you did a lot of free work. After finishing your free dev work, you also need to be a dab hand at working the politics of a successful open source project, again for free. They won’t necessarily be actively hostile to your pull requests, but keep in mind that Rails Core does not consider 2.3 a priority and signaled strong distaste for the notion of having to do any release management for 2.3 patches even if the code were given to them on a silver platter.

(But horsepuckey, you’re not going to write free patches for Rails 2.3, or you’d have commits you could point to demonstrating your willingness to do this over the last 6 months.)

“You’re using your evil marketer wiles on me in pursuit of your selfish interests!”

I am, indeed, attempting to get you onto Rails LTS rather than unpatched 2.3. Why? Because as a fan of Rails and long-time member of the community, whose business has benefited enormously from it being available, I do not want to see other community members get rooted.

I have no direct financial interest in you deciding to buy a support contract for Rails LTS. I don’t get a commission and I’m not an investor, I’m just the anchor customer. My $10,000 is where my mouth is. Well, no, my $10,000 is presumably sitting in a German bank account, but you get the general idea.

How Do We Switch?

It’s all on their website. Switching to the community edition (free) is a one-line change in your Gemfile, and you can and should do that today if you’re already on 2.3.18. (If not, upgrade to 2.3.18 first. Then, have a frank discussion about security priorities, since you should have been on 2.3.18.) To get a support contract and your username/password to access their private git repository (which gets the patches immediately on release rather than 10 days later), get in touch with them via the website. When I did it it required a paper contract and a wire transfer to Germany, so it won’t complete as quickly as git clone will, but you’ll be on the way to getting this resolved before the next round of patches drop.

P.S. Remember, you need to have all of your Rails apps patched continuously, not just “the main one.” If you miss e.g. a staging server, a simple service which hooks into the main app, an analytics side-project knocked up by an intern, or an old installation of Redmine, then that box will be rooted, and if that box is inside your firewall you can basically assume you will lose ever box attached to it.

Recent Comments