Hiya guys. My good friend Keith and I decided to do something a little different and tried recording a podcast. We’re still rather new at this, so it took for form of a freewheeling conversation. Major topics included:

- the experience of working at large and small tech companies in Japan

- the Japanese web application market

- career advice for

programmers don’t call yourself a programmer

- us trying to sell you on starting A/B testing

- conversion optimization stories, including actionable tips which have actually worked for people

- a wee bit of generic geekery.

The podcast weighs in at about 79 minutes long.

Podcasts take a metric truckload of work to put together. If you like it, please, say so. If folks have interest in it, we’ll do it again. If not, well, one more data point as to what the market wants.

Podcast Link (M4A. Click to play, right click to download. The play feature may not work quite right in Chrome. Feel free to put this on your iDevice. (You may find this URL helpful: http://www.kalzumeus.com/feed/atom/ That technically includes all the posts on the blog, but iTunes and similar software will automatically pluck out the audio ones.)

Podcast Link (MP3, for Chrome. Click to play, right click to download.)

Transcript (Because We Love You)

Patrick McKenzie: Hi, everybody. I’m Patrick McKenzie, better known as patio11 on the Internets. This is my buddy Keith.

Keith: Hi, I’m Keith Perhac. I live next to Patrick’s and I’m pretty much unknown on the Internets.

Patrick: So when we tell people we’re right next to each other, we’re right next to each other in Ogaki, Japan. How the heck did we end up here?

Keith: Long, long story. So I’ve been here for nine years, you’ve been here for eight, pretty much. And we came here on the JET program. I was working as an English teacher, you were working at Softopia, which is apparently our prefecture’s gift to web development and iPhone development right now.

Patrick: Yeah, the prefectural technology incubator.

Keith: That was an interesting little incubator because it’s been losing money for the last seven years. And then when the iPhone came out, all of the iPhone developers and everything moved in there because rent is cheap. And suddenly the incubator is making tons and tons of money thanks to iPhone apps.

Patrick: Yeah. That was crazy. The number one, number two, and number three most popular Japanese iPhone apps of all time were literally right next door to each other, all in Softopia. They’ve been saying that they were going to make Sweet Valley, the name of this region, into the Silicon Valley of Japan. And I always thought it was a pipe dream. And now we have three successful software companies in literally like a 10‑square‑meter space in one building here. [Editor’s note: Perhaps not quiiiiite Silicon Valley yet…]

Keith: Yeah.

Patrick: It blows my mind.

Keith: Yeah, essentially we’re in the Kansas of Japan. There’s nothing here, like literally nothing here.

Patrick: Yeah, the engineering culture of this region is much less startup‑friendly than say a Silicon Valley or a New York would be. It’s dominated by one monopsony employer of engineering talent, which we’ve both had business dealings with.

Keith: We’ll just say a very large automaker which everyone knows of and who pretty much pioneered the idea of kaizen, which I’m sure you all know of right now.

Patrick: Yeah, the big buzzword for the lean startup movement was lean manufacturing before it was lean startup and before it was lean manufacturing it was just the [REDACTED] way. Whoo, shoot.

Keith: [laughs]

Patrick: Sorry, we’re editing that out.

Keith: The T way.

Patrick: Yeah, T. A big T-Corp here. Somewhat surprisingly, T-Corp and its various affiliated industries don’t really apply the T-Corp way to software development, do they?

Keith: No, and I think the real reason that they don’t do that is because software development is not seen as a manufacturing process. It’s really seen as this kind of artsy‑fartsy kind of thing here. And it’s interesting because Web is definitely seen as artsy‑fartsy, and programmers themselves are pretty much seen as code monkeys.

Patrick: Yeah.

Keith: They’re seen as people on a factory floor that can… you just give them the spec and they punch out the pieces and that’s what programmers are for. And so what you have is a lot of managers who are used to managing assembly lines then trying to manage software projects in the same way. And it doesn’t really work quite as well.

And unfortunately, when big T feels that way about programmers, you find out that all their subsidiaries and everyone who works for them and everyone who deals with those subsidiaries and everyone who deals with the people who deal with those subsidiaries, the whole sort of culture kind of filters down to that.

Patrick: This is true. Even at my old day job, which was a multinational corporation in Nagoya, which there is no company in Nagoya that does not have business with the big T in one way or another. It’s like Detroit times 1,000.

Keith: Very true, very true.

Patrick: Everyone is connected with the automobile manufacturing industry here. Even if you’re not directly connected into your day‑to‑day work. And it trickles down into things like the way engineers are treated, the way the discipline is treated, and the prevailing salary and wages for engineers here.

Even at a large multinational corporation as a salaryman, which is a full‑time employee who is expected to be at the company until death do you part, the wages for programmers are not that great here. Would you say the algorithm is $100 per year of age, per month, give or take?

Keith: About that, yeah.

Patrick: So Keith and I are right around 30 right now. That means we’d expect at a regular company here to be making $3,000 a month more or less, which as you might have seen is a wee bit less than you guys get in Silicon Valley.

Keith: Yeah. Now I do have to say, the pricing structure for payments for programmers and for anyone really, is a holdover from the bubble days. And when you retire, you are guaranteed a very nice retirement fund. And every year because the company will do so well, you’ll get a big, fat bonus check, sometimes three times a year. And the problem is that Japan has been in a recession since about what, I think it’s ’90, ’92, something like that?

Patrick: Yeah, somewhere in there.

Keith: Long, long recession. And we don’t get bonuses. There’s no more job security for this until you retire at 60, now 65, soon to be 70. So we’ve lost all the benefits of working for peanuts at these companies and yet we’re still working for peanuts. That’s pretty much what it comes down to.

The salaries have not evolved with the change in Japan’s social contract, pretty much.

Patrick: Mm‑hmm.

Keith: We had a social contract where you go onto a company and they will take care of you until the day you retire and now it’s you go into a company and it’s pretty much hit or miss.

Patrick: Now, for the peanut gallery that doesn’t know, the peak of the salaryman/lifetime employment system was in about the 1970s or so. And at that time it was about 30 percent of the Japanese labor force who was both working in a large multinational corporation and had this particular seishain [editor’s note: “full company employee”] status that we’re talking about. The rest of the 70 percent were not subject to the lifetime employment guarantee including, most prominently, women.

Keith: Women, yeah.

Patrick: Who we have many, many stories about how Japanese companies do not treat ladies right.

Keith: That’s for a different time.

Patrick: Yeah, another time.

Speaking of the social contract, a lot of Japanese society is built around this presumption that if you go to a good school you will get a good job at a nice megacorp like T-Corp and then have this lifetime employment guarantee. That’s one of the reasons it’s so hard to hire for startups out here, because basically you get one shot at that brass ring of lifetime employment and if you don’t take it right after you get out of the university, you are damaged goods for the rest of your life.

Keith: Well, I do want to cut in there. That’s not really how it works, but that’s how everyone thinks it works.

Patrick: I agree with both parts of that statement.

Keith: And the problem is when everyone thinks that’s the way it works, especially for people who have just gotten out of college and don’t know what it’s like in the world, they’re going to go where it’s a safe bet. And we’re talking about lifetime employment and stuff and how that’s no longer a guarantee. However, if you get into a place like NTT, which is the phone company, even the big T, in most cases if you are a proper contracted employee, then you will probably be there until you retire.

Patrick: Right.

Keith: However, there are only a handful of those companies left. I would say that there’s less than 100, maybe less than 50 in all of Japan that are large enough to really be able to take care of you for your entire life like that.

Patrick: And there’s definitely a difference in statuses at those big companies. For instance, one of the ways they manage to have a lifetime employment guarantee is that T-Corp has this… it’s like an industry within an industry of supporting companies, built around themselves, like suppliers, vendors, that sort of thing.

And while they won’t cut their employees come hell or high water, they’ll cut their vendors like nobody’s business and/or tell the vendors, “Listen, we can only afford to pay you a quarter of what we did last year, so make the appropriate adjustments.” And then the vendors will go down and cut their regular employees or, most commonly, cut their contractors.

Keith: And T-Corp themselves have a lot of contractors. And when you think of contractors, you usually think of consultants or stuff like that. I’m talking about contract employees working on the assembly lines and whatnot. And those people do get cut.

Patrick: Right, for example, right before the recent economic crisis, which is known in Japan as the Lehman shock for some reason, right before the Lehman shock there were about 6,000 foreigners, mostly Brazilians, living in our town of Ogaki. And so I go to a church out here and after the Lehman shock for about a year, every week at church we had a family X or a family Y or family Z having lost all the jobs in the family is going back to Brazil. So that population of foreigners, who were almost all contract laborers at the local manufacturing industries ,went from about 6,000 to about 1,000 in a little less than a year.

Keith: That was a heavy, heavy downturn. But that gives you a pretty good idea of what the labor force is like in Japan. And why it’s difficult to get a good startup community here. I go to a lot of programming conferences and stuff and we really, as programmers, picked a really crappy place to be, to be perfectly honest, because the entire area is ruled by T-Corp. Also, there’s just a very different way of thinking about business in Nagoya in the Nagoya area than in, let’s say, Tokyo and Osaka. And even for Japanese people, and other Japanese programmers, looking at Nagoya they say it’s very difficult for people who are not in Nagoya to start a business here. And it’s very difficult for new businesses to start here.

Patrick: So we’ve been doing this for the last couple of years and we know how it actually works, but people in America always tell me I’m lying when I talk about working conditions for professionals in Japanese societies.

Keith: [laughs]

Patrick: Why don’t you tell me about those lies I’ve been telling for the last couple of years. Just sketch some out.

Keith: So I’ve heard some of the lies Patrick has been telling all of you and I have to tell you that I don’t think any of them were actually even slight exaggerations.

Patrick: Well, let’s recount some stories, shall we?

Keith: Let’s recount some stories. So coming home every night at 12:30 AM, if you could get home.

Patrick: Right.

Keith: OK, that’s definitely true.

Patrick: Last train of the day is 30 minutes after midnight, I missed that train quite a bit of the time.

Keith: Yeah, the business hotel near the station actually knew Patrick by name and face. And Patrick had this thing Tuesdays where there were longhalf‑day meetings.

And so you get pretty much nothing done on that day. So you’d have to work until about 12:30, 1:00, end up missing the train and he would arrive at the business hotel and they would have a room ready for him. And if he wasn’t there one week, then in the following week when he did show up, they would ask, “Why weren’t you here last week?”

Patrick: It got so bad at one point I left my Kindle there overnight on a Monday and it was waiting at the front desk for me the following day with a note, this is Mr. McKenzie’s Kindle, he’ll be in, it’s a Tuesday.

Keith: So really, no exaggerations about the workload. And I, fortunately, was not as bad as him. I could usually get home every night. I usually got home around 11:00 or so. So I was very lucky to get home at 11:00.

Patrick: So what are we doing for this 12‑to‑19‑hour day? Is it actually programming for the entire time? No, not so much.

Keith: OK, so Patrick and I had very different employers. He worked at a very large, how many people were in your company?

Patrick: Well, let’s see, at my office there were about 70, but companywide maybe 1,000‑1,200 employees or so.

Keith: So he’s with a very large company that does only programming. I, on the other hand, was in what is pretty much the Japanese startup. A startup is called a “venture” here. It’s generally a single person putting his money on the line, getting a loan from the bank, and trying to make a company out of it. I was the only programmer at this IT company. So we were a company of around seven or eight people, and I was the only programmer left after my boss, the other programmer, quit.

So pretty much I had a lot of free rein in what I was doing, but, on the other hand, for any product that my company had to ship, I had to make it from scratch. And that’s not just programming, that’s the design, development, graphic design, figuring out what the customer wants, how we’re going to accomplish it, pretty much everything. The other people in the company were sales and management.

Patrick: My company was a multinational consultancy. Think of like an Accenture or IBM, which goes to a client and say, “Hey, we’ll fix your problem, whatever the problem is, and we’ll sell you smart people to make it happen.” We were in the wetware business. I was the least wet bit of the wetware, we’ll put it that way.

My official title was “System Engineer.” That’s one of these things in Japan, programmers are considered code‑monkeys, but system engineers, who tell programmers what to do, are assumed to have a bit of discretion and professional ability. Maybe half the company was people in sales or support, who would sell a university on, “You should use our systems for doing your backend course management or payroll or whatever.”

Then the other half of the company was the engineers like myself who would talk to the customer and figure out what they actually needed for integration with their systems and then build out the code to do it. Or assist outsourcing operations for outsourcing the business process management to low‑wage countries like India.

The feeling in the company was that even though we were a software company, writing software did not add value. That’s almost a direct quote from the CEO. So, we would figure out the software that needed to be written and then actually get the software written by cheap people because that would provide more value for our customer.

This resulted in me doing outsourcing management to India for about three years because I was the only one in the company who could speak good enough English to manage it. That was an experience.

Keith: You had actually told me about some of the technical docs that they had sent before you were on the project where they would actually put the Japanese technical docs into Google Translate and then just ship them over.

Patrick: Yeah. I tried to stop that and was less successful than I wanted to be. At one point I told my boss, “Listen, boss, we’re shipping out several thousand pages of technical documentations for this particular subsystem which just absolutely puts the ‘critical’ in ‘business critical.’ You need to clear the next month of my schedule so I can translate them.”

He said, “Your fully loaded cost as an engineer is about $6,000 a month [ salary of $3,000 times a factor of two for contribution, taxes and other overhead involved with hiring me]. $6,000 a month is too much to pay for translation. We want to get it done for about $4,000, so we’re going to have an Indian company to do the translation for us.” I said, “I don’t really love that plan, but I’ll do it. But I want to spot‑check the quality of their translation just to make sure we’re getting our money’s worth.”

The first day I get back an Excel file. I can’t remember exactly what the error was, but on the first page that was describing black as white, a clear error. I mail the Indian subsidiary and say, “Hey, I was spot‑checking the quality of your translation and there’s just this glaring error on the first page that makes me worry about the rest of the documents. Can you please tell your translators to be careful.”

They mail back to me a few hours later, “We don’t agree this is an error.” It’s literally a translation of black is white or something. So I mail back, “This is absolutely an error. I haven’t had the opportunity to discuss it with a native speaker of Japanese, but there’s no possible way that your translator is translating this correctly.”

I get a mail back, “We don’t agree.” I said, “You need to put your translator on the phone with me now because we need to discuss this. The project will not proceed if you have this level of understanding of what the requirements are.” They said, “We discussed with three authorities and all of them agree with our translations. So you’re outvoted.”

I said, “Who are your three authorities?” They said, “Google Translate, BabelFish and AltaVista Translate.” So I was outvoted by three computers who all use the same dictionary apparently. That sort of thing happened all the time. They had billed us literally $4,000 for having people do the manual copy‑pasting work into Translate and billed it as translation services. Yeah. That project didn’t work out very well.

Keith: I actually want to jump back real quick. You had mentioned the difference between the System Engineers and programmers. You had a blog post, I think it was two weeks ago and it got put on Hacker News. Everyone was like, “Oh, I’m a programmer, so that’s what I’m going to call myself. I’m not going to call myself System Engineer.”

This is really one of the places where it’s a very clear‑cut difference. It doesn’t matter what it is that you do all day. A simple name change raises your pay grade pretty much double. The amount of things that you are trusted with, the amount of things that is decided that you do. This is not to say that programmers are not given system engineer responsibilities, they’re just not believed to able to accomplish them.

Patrick: Right.

Keith: So, it doesn’t matter what you’re doing in Japan, as long as you’re a programmer, call yourself a system engineer and you’d double your pay.

Patrick: Right. Actually every time I had a bug for about the first two years of working on a company, often because I didn’t quite understand the requirements in the document because all the documents are in highly technical Japanese. And my co‑workers would be berating me for the bug or the absence of testing, which failed to reveal the bug. Or just being careless, because I’m often careless. They would say, “Listen, Patrick. This isn’t acceptable, you are not a programmer. This should have been taken care of.”

Definitely with regards to Japan, call yourself a system engineer if you have the choice, even with regards to America.

I do programming, I like programming, I love programming. The craft and actual activity of programming really, really appeal to me. But as a consultant when I’m talking to businesses, I never describe the value that I’m adding to the business as, “OK. I’m going to program some stuff for you in Rails.” Because businesses don’t really see it on that same level.

Even businesses that are run by really engineers’ engineers, like the Fog Creeks of the world, which really love programming and the craft of programming: at the end of the day they are a business. So you need to be connecting to them on that business level of, “Here are the concrete benefits you’re going to get from doing this engagement with me.”

Keith: It’s just like when you sell a product, you don’t sell the features, you sell the benefits.

Patrick: Right, right.

Keith: You are programming, and that’s the feature that you’re selling. But that’s not the benefit. The benefit is not, “I’m going to write code for you.” The benefit is, “I’m going to make a system that does this awesome thing. And this awesome thing is going to make you a million‑up in dollars.” And that’s what you sell. That’s why you call yourself a system engineer instead of a programmer.

Patrick: Or providing solutions instead of providing software.

Keith: Solution Architect. It was so funny. My job title in my company has changed so many times. I think it changed seven or eight times in the last four years. And my favorite one was “Solution Architect,” because it just says nothing about what I do whatsoever.

Patrick: But civilians, or whatever you call people who aren’t engineers, sometimes respond to things like what is printed on your business card. That being the reality, adjust yourself to the reality rather than what you think your ideal world would look like.

Keith: Yeah. Really, if you want to put “programmer” on your business card, write it in binary on the back or put it in as part of the design or something.

Patrick: Right. You can always call yourself what you want when you’re around just us geeks, but when off Hacker News and you’re talking rate negotiations with customers, adjust to their view of the world. It will make you happier in life.

Keith: Exactly, exactly. Don’t believe us, A/B test it. I actually did this. I went to a prospective client with a programming friend of mine. We do the exact same thing. We have the roughly the same levels of technical and business acumen. We decided, “Hey, we’re going to try this out.” He called himself a system engineer, I called myself a programmer. For the rest of our meeting they deferred to him over me for every single thing. [Editor’s note: You’re right, this is not an A/B test.]

So just changing that one little word on your business card or when you introduce yourself makes a huge difference. It’s really just you have to change yourself to fit your customers’ expectations.

Patrick: Obviously the culture of businesses in Japan is very different than what many of our listeners are used to. Well, I say the culture of Japan: Japan is a big place. It’s like saying, “the culture in America.” Kansas is a different place than Texas, is a different place than a tech startup specifically in Mountain View, California. But the business culture of, say, metropolitan Nagoya, Japan is very different than the business culture of New York City, or at a tech startup in New York City, or at a financial services firm in New York City, or specifically Goldman Sachs in New York City.

You have to adjust yourself to whatever that particular situation you find yourself in. That being said, there’s very, very few places I’m aware of calling yourself a programmer is a career enhancing move.

Keith: Yeah. Let’s stop berating everyone for calling themselves programmers.

Patrick: Right.

Keith: What do you say? You want to move on to kaizen?

Patrick: Sure. Let’s move on to kaizen.

Keith: OK. Everyone, I’m sure, knows kaizen.

Patrick: Actually, I don’t think that’s true. Why don’t you explain what kaizen is.

Keith: Really? Because I got a photo from one of my friends in Nashville of all places. She went to a burger joint and had the Kaizen Burger. This huge burger with Kobe beef and cheese and all the stuff, and they just called it “Kaizen Burger.”

Patrick: That sounds delicious, but I think the rest of America is not caught up to Nashville yet. So let’s go.

Keith: Everyone should catch up with Nashville, I swear. [laughs]

OK. Kaizen is a term in Japanese which means “improvement.” That’s the general translation. What it has come to mean in American English is the reiteration and iterative improvement of systems and processes that were founded pretty much by Toyota. Essentially it’s reiterations over a design in order to get rid of flaws and to make a better product.

This is pretty much the the cornerstone of any physical manufacturing process. Any car that you see is built with kaizen. Apple does it with their Macs. Everything is iterated and iterated. They make a design, they put it out there, they find out what’s wrong and they slightly change it, they slightly fix it and they keep reiterating and reiterating. Then they finally get a great product. That’s how Toyota has worked, that’s how most manufacturing works.

Patrick: I think this idea is so powerful. There have been hundreds of volumes written about the Japanese economic miracle. Honestly this and the related Toyota process improvement were so powerful that they were able to cover up every mistake made at the same time. If you have that going for you and the rest of the world hasn’t caught on too it yet, you can do all manner of stuff totally stupidly, like work your people to near death by exhaustion. You’ll still ROFLstomp over the competition.

Keith: Exactly. Where kaizen comes in to our conversation now is that kaizen has left the physical manufacturing world and is starting to go into the software development.

Patrick: If you read Eric Ries’s book The Lean Startup, which by the way is a fantastic read and you should read it if you haven’t already, it’s one of the ideas he touches on a lot.

Keith: Yeah, yeah. I actually want to pick up a copy of that. I saw that in your house when I was over there.

Patrick: One of the ways that kaizen is relevant, not just to people who are manufacturing physical products but also to software developers who are making software or an experience delivered over the Internet, is that we can do things like A/B testing. So we can tell in almost real‑time which of multiple versions of a website, once exposed to users, causes those users to have a happy experience. You could define “happy experience” in a few ways: judged by business goals like whether they buy more software or sign up for your email list more often, or judged by whether they achieve success with your software.

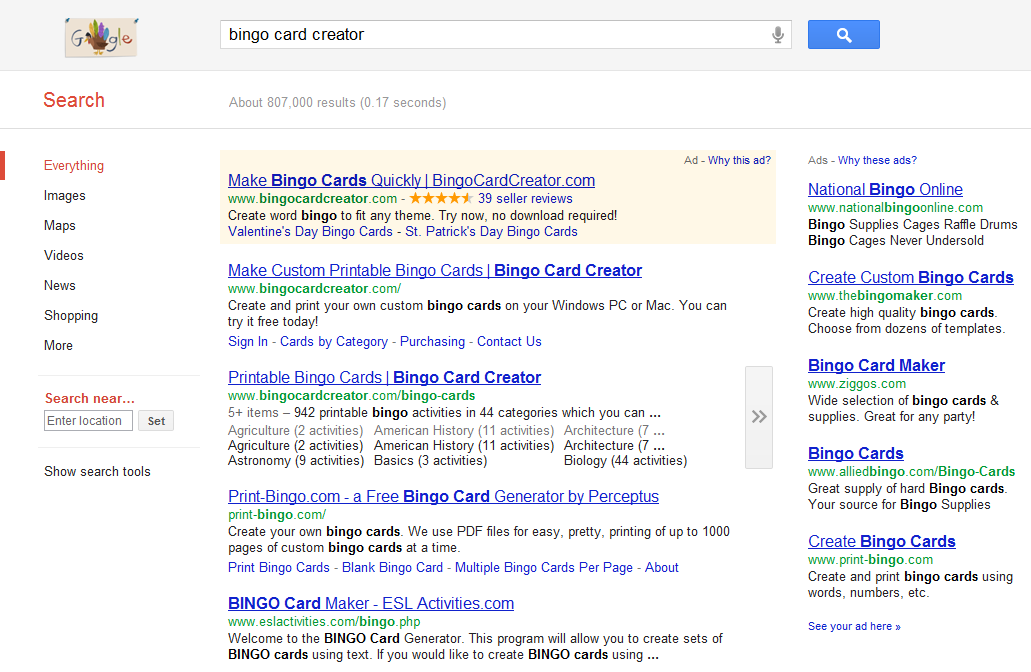

For example, I sell software that makes bingo cards for elementary school teachers. If the schoolteachers can’t successfully make bingo cards, that’s a problem for me. So, I can redesign the interface of my software such that they actually achieve task success.

Keith: The great thing about this iteration, when we’re dealing with software and especially web apps, is that the feedback is so immediate and the cost for doing these iteration tests, these split tests is so low. How long does it take you to make a split test?

Patrick: One line of code, it’s the only way to do it.

Keith: One line of code. All right. In one line of code you can test which creates the better user experience.

This kaizen originated in manufacturing. In manufacturing, it’s a much more expensive process. You have to build it, which means you have to use the raw materials, you have to create the building process, then you have to ramp up production and ship it to the customer and the customer has to give you feedback. We’re talking, maybe, two or three years to get feedback on a single design before you can iterate.

Now, we can iterate… If you have enough users on your site, you can get an answer with a split test in about a day.

Patrick: At Facebook or Google scales you can get it literally in seconds. Even at fairly minor scales, like the Bingo Card Creators of the world, I can throw out a test every Monday and have a statistically confident results generally by the following week. It’s a wonderful thing when you don’t have much time to work on a site.

If you’re getting about a hundred visitors a day then you can throw some up, come back a week later, and have results. Doing the A/B test doesn’t block any of your other activities for the week. You can continue talking to customers or continue writing documentation, continue producing the new feature. Then, when you’re ready for it, take a look at the results of the A/B tests and generally just make a one click to pick result A over result B or whatever the stats tell you to do.

Keith: What we’re actually seeing… Patrick’s A/B testing software, he made it himself. It’s called A/Bingo. It’s amazing and you should pick it up. I use Visual Website Optimizer, which is a great software, all JavaScript based, works on any page, I recommend that as well.

But what we’re seeing is a change from manufacturing where in manufacturing you can have a thousand ideas, but your iteration time is around maybe six months at the fastest, a year, maybe two or three if you’re talking something huge like a car.

With the software iterations, one line of code takes me five minutes to implement. VWO does the same thing, it takes me 5‑10 minutes to implement. What takes more time now is to actually think of what we’re testing. The time it takes to test something is so infinitesimal that thinking up good tests takes more time. Which is amazing that we’re in this technological area that we can test things as fast as we literally think them up.

Patrick: Right. Also it prevents a lot of waste in the company. Have you ever been a really pathological meeting? I once had a six‑hour meeting involving four people to discuss the text that was going to be placed on a button for signing up to a mailing list. The mailing list was only getting 50 sign ups a week anyhow. There’s an actual cost to that. The fully loaded cost for that meeting was on the order of $300 an hour times six hours, so almost $2,000 spent just to determine the call‑to‑action on a button that didn’t really matter anyhow.

If you have a culture in your organization of testing things, that would literally have been a 45 second discussion. Like, “I think it should be, ‘Sign up for mailing list.'” “I think it should be ‘Sign up now.'” “OK. We’ll throw it in the test.” Done. And you save that $2,000 and spend it on stuff that actually matters to your business and your customers and the world at large.

Keith: Yeah. Going back to the Japanese side of things, this is a big thing where they don’t consider software to be a manufacturing process. Testing in Japan… Now, we have unit testing and testing like that, but the idea of user‑based testing is pretty much non‑existent, almost completely non‑existent. Unless you’re going into the very large, very in‑the‑know tech companies. I’ve dealt with one or two, and they’re not common at all.

Patrick: For example, one of the several big startups based in Tokyo are in the mobile gaming space. There’s an American company you’ve probably heard of, they allow you to make virtual cabbages and water the virtual cabbages. Sometimes the virtual cabbages rot.

This company is very, very sophisticated and they iterative improvement processes including A/B testing and collecting user metrics and what have you. They recently opened a Tokyo office and somebody there said, “Yeah. We’re pretty much planning on effing killing all the Japanese companies in the this space.”

I do not love that company, but I think they’re likely to achieve that goal. Just like Toyota versus the American manufacturers, if there are 10 people in a fight and only one of them understands how to use science, I already know who’s going to win.

Keith: I like that science is the thing that’s going to win the fight. [laughs]

Patrick: It seriously is the revenge of the geeks out there right now. Really.

Keith: Really it is. For the first time in history we have so much data that we don’t have enough people to process it. We have so much information that really what we need to do now is just process all this great information and put it to good use. And we just don’t have the resources yet.

Patrick: Right.

Keith: What we need is mathematicians and statisticians to find, look over, and analyze this data.

Patrick: Yeah. Also, this is a good thing for you to pick up for your career. A/B testing is a skill set that is not really all that hard to pick up. Grab a book, study it for a week. The mechanics are dead simple. After that, it’s just a matter of coming up with what actually to test.

But that skill is fantastically rare, much more rare than, say, skill with creating web apps in PHP or Ruby on Rails. Because it has direct bottom‑line implications to the business, to the tune of, “What’s five percent of your sales for the next quarter?” When you’re talking to a company the size of say a T-Corp or just the line of business from Bank of America’s website, five percent is a very significant number.

If you can routinely quote numbers like that, you are no longer in the $60‑to‑$100‑an‑hour bucket with other programmers, you are in the bucket with strategic initiatives that add five percent to Bank of America’s bottom line. Scary stuff.

Keith: I really hate to keep coming back to this. System engineer versus programmer, implementing an A/B test takes one line of code, takes five minutes to do. If you are the person that used that one line of code, changed the color of a button from blue to red, and added five percent to a multi‑million dollar company’s bottom line, you’re no longer the programmer who implemented that, you’re the guy who added five percent to a multi‑million dollar bottom line. That’s what matters.

Patrick: Right. Billing also scales right to match, particularly when you get clueful clients. I won’t be comfortable talking about mine. Suffice it to say if you have a portfolio website… Not that I have a portfolio website.

Keith: You need to make one.

Patrick: I don’t know. Yes and no. When someone comes to me and says, “Hey, we’d like to hire you for this thing, do you have an example of people that it’s worked for before?” I can informally say, “Well, I’ve worked for XYZ, and XYZ have reported this kind of result.”

That’s, by the way, a trick when you’re dealing with clients… It’s not a trick because both of you will benefit from this. But say, “Look, if we have a successful result with this project, I would like to write that successful result up as a blog post or something. That will be to our mutual benefit, you’ll get additional attention because of me writing the blog post, and I’ll get something to keep for my portfolio.”

Phrased like that, many clients will say yes to it. It is a wonderfully, wonderfully wonderful thing to arrange for yourself as a consultant. For example, when I was working with Fog Creek, when it became obvious that the engagement was going to work out for both of us, I said, “Hey, you guys are always looking for new topics for your blog post, why don’t let me ghostwrite one about what we did for the marketing?”

They said, “Oh, yeah. Let’s do that.” So I wrote something called “Our Marketing Is Up Fog Creek and How We Fixed It” or something to that effect. Where we talked about things like we made changes to the website and as a result Fog Creek’s conversion rate went up by, say, 10 percent. Just make a guess of how much money Fog Creek makes in a year, add 10 percent to that, it’s meaningful, right?

So, Fog Creek is obviously very happy with this. But in terms of dealing with my other clients, when they say, “Oh man, Patrick. That number you just quoted to me is a lot of money. How do I justify that to the investors or how do I justify that to my team?” I say, “Well, if you look at this post over here by Fog Creek, they said I added about 10 percent.” And done, that’s one way to deal with pricing objections.

[Editor’s note: Patrick wasn’t clear on this, but 10% was a handwavy approximation number here. The actual number is undisclosed.]

Keith: And that’s something I’ve been working on with. We were talking earlier about how this split testing your stuff is not known in Japan. I’m trying to bring split testing and modern iterative development practices into Japan.

One thing I found when dealing with my customers is that they feel the same way, it’s like, “How do I add this to my bottom line?” I say, “Well, I improved such and such company, who makes a million dollars a year, by 10 percent.” Sometimes they understand it and sometimes they don’t.

When they don’t understand it I say, “Well, why don’t we do it like this. You pay me half of what I’m charging. And for every percent improvement we see over your current baseline, you give me another X dollars.” People seem very happy about that. Until, of course, the results come in and they end up paying me three times to what they were originally going to pay me.

Patrick: Yeah. Pay‑per‑performance is an interesting model.

Keith: It’s not the best.

Patrick: Yeah, I am not a big fan of pay‑per‑performance arrangements. Not to say I would never do them, but I typically try against them.

Here’s one reason. In any sort of project you have execution risk. Generally as a consultant you want to be responsible for your own conduct, but not risks external to your own execution. If, for example, you want to do a pay‑per‑performance arrangement for search engine optimization or for A/B testing or conversion optimization for a startup, that startup’s priorities might change on a dime. This can happen one week after you get out of the building. That actually happens frequently. The project you were working on can get shelved. This even happens at multinational corporations.

If this happens, you’re not going to make your pay‑per‑performance numbers no matter how good the quality of your underlying work. Typically, with a pay‑per‑performance arrangement you’re going to be getting a smaller number upfront, plus a payment if you hit particular milestones. You won’t get that milestone payment and you’re going to end up working for a fraction of your rate. And working for a fraction of your rate is not the purpose of the exercise. Unless it was client who had a clear reason not to pivot on the…

Keith: Right. I should have prefaced that with saying that these are clients that I have had worked with before in my previous companies and that I do trust. And who I know are not going to shelve the entire project and I’m going to get put in the works.

These are things that part of the contract of doing the performance‑based payment is that I’m going to be setting it up and they are going to be putting it out there and that it is going to run. Like you said, it’s not a 100 percent, nothing’s ever 100 percent. But I would never do it especially for a large company that I’ve never worked with before, I would never do a performance‑based review. I don’t think.

Patrick: Right. Engineers have a funny notion of what the price of things is. If I say “$3,000″, that sounds like a lot of money for us because, hey, we worked for months for that. But $3,000 for a real company that has real assets and real employees, that’s literally below their capability of measuring stuff. It isn’t a line item on the annual report, it isn’t even in the appendix to an appendix on the line item of the annual report. You really have to get into the five‑figures to even hit on the radar screen at all.

Given that, if you were thinking, “OK. We’ll could charge a variable price between $3,000 and $15,000, or just charge $20,000 fixed,” there’s a lot of businesses that will say, “Give me the higher $20,000 price, because that will make my life easier. Getting a variable charge approved through the accounting division or my higher‑ups or whatever is going to be more difficult, because that’s not our established process.”

If it is just a fixed $20,000 coming out of budget X, well, budget X has hundreds of thousands of dollars in it because there’s employees in there, too. [Editor’s note: Employees are very expensive. There is a cynical but true saying: “Overhead walks on two legs.”] So $20,000 out of that budget is not difficult to approve.

Keith: Right. Working, not with T-Corp in particular, but with other companies of that size, we would have our sales reps on their side come to us and say, “Our budget is X amount of dollars. Make it under that.” That’s not their maximum possible budget, that’s the budget they have before they need additional signoffs. You could spend within $1 of that, and it would be no problem. However, if they go over that line, they have to get the sign off of their manager or, god forbid, the vice‑president or someone. As long as it’s under that number even by a dollar, they can sign off themselves and that makes their lives so much easier.

Patrick: You were saying something interesting earlier, which was that you hope to bring in A/B testing and these modern techniques into Japan. That’s something I’ve heard a lot in working with my other companies, because the Japanese engineering, with specific regards to, say, Web engineering, is kind of lagging a couple of years behind the U.S. right now, right?

Keith: Oh, so far behind.

Patrick: Let’s talk about the status things. So the Joel Test is getting almost 10 years old now.

Keith: Is it 10 years already?

Patrick: Almost 10 years I think. [Editor’s Note: Even older!]The Joel Test is about basic things like source control, having a quality department, yada, yada. Japan, not quite there yet. So I worked with a company that worked with other companies. We had source control, thank God. Subversion, though, not git. Sorry, I didn’t mean to be a snobby geek there. Subversion is an excellent source control system. It’s heads and tails better than no source control system, which is the competition here in Japan.

Similarly, we write big freaking enterprise applications in Java with homegrown web frameworks, which were absolute pain in the butts to work with. One of the reasons I have like 60,000 Hacker News karma was there was a compile and deploy step that literally took like five minutes to run. So if I wanted to change, say, the number of columns on one particular table on a page, testing that would take upwards of an hour. Oh, whoops, I had a one‑character bug in my HTML, rerun the compile. It’s going to take five minutes. Yada, yada.

The amount of friction involved in that process destroyed my productivity. [Editor’s Note: It didn’t help that I’m fundamentally a lazy git.] However, we measured productivity by number of engineering hours expended, so by that metric I made my department look very good. But modern web frameworks like Ruby on Rails, Django, all the fun stuff, make life so much better.

Keith: It’s really ironic that Ruby was created by a Japanese man, and yet Ruby on Rails is pretty much unknown here.

Patrick: Maybe this will change a little bit. I think EngineYard has hired Matz, right?

Keith: Right. Was it EngineYard ? I thought it was Heroku?

Patrick: Yeah, it was Heroku. Sorry. Heroku by the way, is the most Japanese name on an American company I’ve ever heard. [Editor’s note: I heard at Startup School that they were explicitly inspired by the Japanese aesthetic… in case the samurai and Godzilla on the pricing page had not clued you in yet.]

Keith: Yeah. I know. But actually there are Rails conferences here and it’s getting more and more popular. The problem is that web apps themselves are still not that popular here. I think part of that is done in by the fact that, there are maybe four or five countries in the world that have IE6 shares above 25 percent. [Editor’s note: I don’t know about this one, but wasn’t sure enough to correct him.]

I believe they include Thailand, China, and Japan. China actually has I think 23 or 22. It’s really quickly dropping. But Japan still relies on IE6 so much. And the reason for this is that back when IE6, when XP came out, we were still, not really in the recession, but we still have a lot of money as a country. And so everyone had their IT departments, and everyone had these huge reduxes and they made all their systems compatible with XP. And it was great and wonderful. And then the money starts drying up, and the first thing to go is the tech departments.

I’ve worked with couple large companies that literally had outsourced their entire IT departments. And so there was no one at the company anymore who could even do anything. Let’s say they needed a new computer setup or new proxy or one of their NATs died or something, there was no one at the company who could fix that.

Patrick: That brings up a great topic. You’ve probably heard that engineering productivity is worth pretty much any amount of money relative to engineering salaries. Everyone tells you to get two big wide screens, as it’s only 400 bucks extra.

Despite my previous employer being a software company, they had outsourced the internal IT. So then rather than buying each programmer a computer, they would lease a computer through blah‑blah‑blah, whatever, for 80 bucks a month. And by default, it was a years‑old computer with, let’s say, one gig of RAM, a processor from 2003, and a 14‑or‑15‑inch monitor for a desktop system. And there was literally no button you could push at the company to get a better computer than that.

Keith: Once the rules are set, it’s not worth the bureaucratic hassle and even the time to think about to change it in a company. What it does, in the end, is it just hurts everyone.

Patrick: Another factor about web apps in Japan is that a huge portion of Japanese use of the Internet is not actually on real browsers, it’s on the lovely fake browsers that you find in old pre‑iPhone Japanese feature phones. That’s an entire topic in itself. Japan, hardware‑wise, were probably the most advanced cell phones in the world until…

Keith: Also software‑wise. When we were still dealing with WAP and wedge TML and WEKO, WACKO, WACO, WACO, whatever the hell we had back in early ’90s and stuff, Japanese cell phones had iMode, which is a full-featured HTML subset, and they were browsing websites in ’91. On their cell phone.

Patrick: Websites with pictures and JavaScript. It was amazing. And then it didn’t really change for like the next 15, 16 years.

Keith: Yeah, they’re still browsing the same Web pages 20 years later.

Patrick: Yeah. They call this the Galápagos effect. Like the Galápagos Islands, which have a variety of different finches that are found nowhere else in the world, Japan had a variety of very advanced hardware platforms found nowhere else. The software for each of the hardware platforms would be literally handwritten assembly each time a new model came out. That was the dominant way to do cell phone development, with improvements like, “OK, we’ll put a JRE on it and allow you to run Java code.” But that was the dominate cell phone paradigm up until the iPhone came out. And the iPhone proceeded to ROFLstomp over the Japanese carriers. Right?

Keith: Pretty much. Pretty much. And now we have Android phones as well — a lot of Android phones. The problem is, and I think it’s pretty much the same in America right now, is that you don’t get the updates. The Galápagos model is still the common way of thinking for any cell phone besides the iPhone. So you have this Android‑based amazing phone that is outdated in one to two months. You will never receive an update for it through the life of the contract.

Patrick: Just a feature of the Japanese consumer electronics market. People tend to upgrade devices very quickly here.

Keith: Very quick. Very quick.

Patrick: Japanese cell phones are marketed under the assumption that the core of the market updates their cell phones at least yearly.

Keith: Yeah. In America, because everyone is on the two year contract, the companies assume that you’ll update your phone when you’re two year contract is up. And in Japan, even though there’s a two‑year contract, most people update their phone, I would say, once a year. And depending on how trendy you are, even more.

Patrick: One of the main early adopters for the cell phones in Japan, and I swear I’m not making this up, high‑school girls.

Keith: Oh, yes.

Patrick: Their use of the phone as a mobile/Internet platform drives quite a bit of the development here. I can never remember which of the companies it was, but a couple of years ago when smartphones were starting to get popular, one of the companies was literally pitching them as a fashion accessory item.

So in addition to pitching, “It has a camera. You can take photos with your friends. And here’s what the software does.” They would pitch like, “And here are the varieties of things you can stick on the phone to make it look different but similar to your girlfriends’ phones. This way, you can be trendy in your own individual-but-not-too-individual way.” [Editor’s note: If you think I’m cynical about the social motivations of teenage girls, you should hear me talk about geeks.]

Keith: Right. And they’re starting to do that with the Androids now. So each of the Androids has pre‑installed software for each kind of clique for the Japanese high‑school girls. It’s really interesting to look at. It is a bit depressing as a programmer. It’s like, “You could just customize the wallpaper yourself and not have to pay the $600 for the new phone.” But, oh well.

Patrick: Yeah. Meet the customers where they’re at. Right?

Keith: Right. Right. Do we want to go on to websites as… I still not have been able to figure out how to really put this other, not in Japanese.

Patrick: Well, say it in Japanese and I’ll translate for you.

Keith: Now I’m going to forget it in Japanese. What was it? Ore ore homupeiji kind of thing. [Editor’s note: The rough sense of this: “Me-me-me home page!” ] So what it really is, so you have the ore ore framework. It is the framework that you built, and you love to death, and is not used for anything at all.

So the web page is pretty much in a lot of cases… OK, here’s how I’m going to say it. The business card web page, I think really is the best way to put it. [Editor’s note: Brochure site, maybe?] A business card web page that doesn’t accomplish anything first of all. And in addition to not accomplishing anything, is made in a way so that the president of the company feels vindicated that he has spent enough money on his web page.

So even if they have like a goal like get customers or tell customers about our company, it’s not something that they’re working towards. They are not investing any time or effort into the home page other than saying, “Oh, we need a home page. I spent $6,000 on a designer to design me a home page in Dreamweaver.”

I think we should talk about those.

Patrick: Let’s talk about this.

Keith: Yes.

Patrick: So we’ve got this idea of having a brochure website for maybe an offline corporation or even for companies that are SaaS Internet startups what not. The home page is not designed for the interests of the business but rather for interests of stakeholders in the business, which are two very different things.

Man, I’ve seen home pages that were literally battlegrounds. There was a war between the engineering department and the marketing department and both sides lost. Engineering said “We want to build features. We don’t want to work on any of that crap on the home page that doesn’t require any technical expertise whatsoever.” Marketing said “We have this message and this brand that we want to get across.” The result of that war was a page that didn’t convert anyone and wasn’t clearly owned by any group in the company.

There are excellent companies which have little dysfunctional issues like this. Engineering’s job is to ship more features to the customer. Marketing’s job is to brand or whatever their magic stuff is. But nobody’s job was to measure the conversions on the page, or to increase those over time.

I’ve gone into very smart, successful, well‑managed companies and asked questions like “So, how many trials did you guys do last week?” And the answer would be, “We don’t know. There’s probably a SQL query we can run somewhere that will tell us that.”

Keith: Yeah. I had a similar thing. This was actually very eye‑opening. I did a reservation system at a really cool place. They have online and phone reservation systems. The phone reservations have a backend to their online system, which the front desk uses to place reservations.

So I could see, when I was doing the analytics for their site, how many reservations they had but not where they came from. I couldn’t see if they were self-service reservations online or assisted reservations over the telephone. So I asked the person in charge. I said, “What percentage is online? And what percentage is phone?” He said, “I think at least 80 percent of our reservations are from online. I only think 20 percent are from the phone.” I said, “Wow, that’s much more than I thought. I thought that the phone would be much, much more popular. And he said, “Yeah, but those are the numbers I think.”

So I installed Google Analytics, and I dug into the numbers. It turned out that less than 20% of their volume was online, and more than 80% was on the telephone. So they had no idea of even the number of reservations that were coming in and where they were coming from. And doing a little more analytics, I found out that those 20 percent were the customers who had survived through the reservation process. The system was difficult to use and the conversion was horrible: only about 15% of people who started a reservation actually got done with making one. That was very eye‑opening for them.

Patrick: It’s easy to laugh at them in hindsight, but I guarantee if you run a business right now, there is some number that is key to your business that you are not tracking and that would be very eye‑opening to you. The one that I routinely bring up for clients is, what percentage of people who use the software/free trial/etc stop using it after the first time, versus what percent use it at least twice?

The number that use it at least twice is almost always depressingly low. When I started tracking it for Bing Card Creator it was only 40 percent of people came back a second time. These days, it’s up to 60 percent, which a 50 percent lift, did wonderful things for my business, but still 40 percent of people would not even give it a second look.

40% is a decent ballpark number for people who don’t track this. That has been fairly consistent across a lot of clients of mine. No one ever gives you a book that says you should be tracking this because it’s abysmal right now and you should improve it, but if you’re not tracking that, I guarantee you it is probably abysmal right now and you should probably try to improve it.

Keith: You should write a book about that. You should just write a book about these are the things you should be tracking, why the hell aren’t you?

Patrick: Yeah, everybody tells me I should write a book, but writing a book is a terrible idea.

Keith: Maybe a pamphlet. [laughs]

Patrick: It’s funny. If I write a blog post people will read it and maybe comment on it for Hacker News. I know it would be forgotten the day after. Ideally, if I wrote a book it would be referenceable by people. Despite the underlying information being essentially the same product, if you put 2,000 words in a book it is perceived as having value, but if you put 2,000 words in a blog post your readers are going to be “TL;DR dude.”

That is the theory at any rate. The reality is that putting 2,000 words in a book is a terrible, terrible use of my time business‑wise. Even if I sell the book (or e-book) at $20 or $50 or $100 a piece, and sell hundreds of copies, that is not a meaningful amount of money relative to getting one of my happy consulting clients on the phone and saying, “Hey, I have an idea that I want to try for you guys. Hopefully it will do as well as the last time. Let’s get this going.”

Keith: However, one thing you might want to try is even just a blog collection and get a physical, printed book. One of my clients, he’s actually considering giving his book away just because of the amount of press it gets him. We did some welcome page tests.

The first one was a picture of him, where he graduated from, and the things that he’s accomplished.

The second one was a big old picture of his book on the “New York Times Bestseller.”

The third one was “I’ve been on NBC” with a video of him in NBC.

The one that says “I’ve done all this” did fairly OK. The one that says “I published a book that was a bestseller” I think was 100 percent better. 100 percent better than that was “I was on TV.” Pretty much once you get on TV, people will buy your shit, no matter what you’re hawking. If you have a clip of you being on TV, they will buy anything you want.

Patrick: This, by the way, is hilariously underexploited by engineers and people in the startup community, but it’s well known among direct marketers. After you have press about you, if the New York Times blurbs about you, even one sentence worth: in all your copy from that point out you put the logo of the New York Times and you say “as appeared in theNew York Times” and that will increase your conversion rate up the wazoo.

You’ve suddenly jumped from “A website that I’ve never heard of and don’t trust” to “Endorsed by the paper of record.” You will routinely see this on some of the skeazier direct marketing pages. Even if they haven’t actually been on the New York Times, they’ll say the product category’s been endorsed by the New York Times.

For example, if they’re hawking a social network, they’ll say “As seen in the New York Times.” They haven’t actually been reported about, but a social network — probably Facebook — has been reported about. I wouldn’t be happy about doing that. That said, if you’re a Fog Creek or a company with is legitimately high enough profile to getink from the New York Times, that should probably be on the website somewhere. Fog Creek has even had their office written about before. [Editor’s Note: Like Lonely Island says, “Doesn’t matter, still counts.”]

I don’t know if that is on their website, actually.

Keith: You should just talk to Joel about that. One thing I do want to say you don’t want to put on your site is “as seen on TV.” Never put “As seen on TV”, especially the red circular logo with all the explosions that you see on $50‑dollar abs stretchers or whatever. That’s not the best thing.

Patrick: Yeah. People may have cottoned on to the fact that that means they paid for an infomercial. However, retrofitting an explanation like I just did is witchcraft. Have your intuitions and have your thoughts about what would probably work for the site. Like we mentioned earlier, it’s so cheap to be test these things, you should be continuously testing them.

Keith: Even if you have a banner space on your home page, just switch out the banners. Do an A/B test with that, switch out the banners, see which one performs better. It’s so simple.

Patrick: It’s so simple and it’s absolutely crazy the amount of lift you can get for an established business that produces value and has been doing so for a decade just by switching out banners.

Keith: Speaking of which, are you going to tell about the recent A/B test result you got from Bingo Card Creator?

Patrick: I should tell about the Bingo Card Creator story, right? OK. I went on a six‑week America tour recently, partly to drum up consulting business, partly to go see Silicon Valley and meet the people I’ve only been reading about in Hacker News, and partly just a change of place. So I went to New York City, went over to Fog Creek, chatted with them a little bit, and while I was in New York City I went to something called Hacker School.

It’s a bunch of people who are learning to become better programmers. They gave me an opportunity to talk to everybody and to teach a lesson on anything I thought they would find valuable. I think a lot of hackers don’t know about A/B testing, so I did a live demo of A/B testing using A/Bingo and I said, “This is literally how easy it is to make an A/B test. We’re going to live code one for my front page right now.”

“I’ve told you in like two sentences what Bingo Card Creator does and for whom. Now, I’ve been doing this for five years and none of you all heard about it for more than 10 seconds, but just throw out a new headline for Bingo Card Creator. Try to beat my champion headline, ‘Make Bingo cards on your computer.'”

Someone said, “Why don’t you try ‘Create Your Own Bingo Cards Now?” I said, “That sounds like a great answer. It won’t possibly beat my best thing, but sure, we’ll just try coding it up.” I come back a week later and there was literally a 40 percent lift. 40 effing percent.

Keith: And that’s on sales.

Patrick: Yeah, that was tracked direct to sales.

Keith: That’s not trials, that’s not, “Oh, I want to know more,” that’s direct sales. 40 percent increase to sales.

Patrick: Yeah. Somebody who knew virtually nothing about my business was able to beat something that I’d worked on for a couple of years. Granted, with A/B testing there’s often a bit of reversion to the mean. You get a confidence interval for whether there’s a difference between A and B, but with the typical way that you do stats with A/B testing, you don’t get a confidence interval on what the percent lift is.

It could be anywhere from say two percent to 80 percent and you wouldn’t know where unless you do more sophisticated statistical techniques that I don’t usually bother doing. Then, that results in a reversion to the mean effect, where a couple weeks later you’ll see it’s only a 20 percent lift now. You think “what gives?” It was probably only 20 percent that whole time, you’ve just got a bit of a ghost in the machine there. [Editor’s note: This is not the only way reversion to the mean can happen. For example, it may be the case for some sites that change itself tends perform well, irrespective of whether the changed version is distinguishable from the old version from the perspective of users who haven’t seen the old version. I generally just ignore the possibility of that, but it is certainly possible]

Be that as it may, you would be amazed how often, big, successful, established companies, like 37 Signals, Fog Creek, Google, Microsoft, et cetera, see huge lifts from A/B testing. They run tests years or decades after having released products and that has a meaningful impact on their bottom line without a huge amount of work.

Something I often tell my clients who have 10‑year‑old products, “How much work would it be to increase the value of this product to your customers by one percent? If you have a team of 20 engineers working on a project for 10 years there’s 200 man‑years invested in it already. You’ve probably already snipped all the low-hanging fruit in terms of features. Making it one percent better by adding features is going to require five man‑years, 10 man years, 20 man‑years of work. Making it one percent better in terms of perceived value can be as simple as changing button copy or changing a headline that you use on your product’s landing page.” [Editor’s note: Remember, the last feature added to the product gets seen by a fraction of a percent of the user base, but the headline gets read by most folks who open the site.]

One percent is definitely not the ceiling. You can get 5, 10, 20, 100 percent in some cases. Basecamp has done many A/B tests, but just tweaking the header on the pricing page was worth 40‑60 percent. That should blow your mind. [Editor’s note: Not sure whether I was remembering my facts correctly here: just trying to Google for a citation, the only article I’m quickly bringing up is a story about Highrise, another 37signals product, getting +30%.]

Think back. A week ago you were doing something for your business, right? What were you doing last week? Did it get you 40 percent to 60 percent improvement in your business’s bottom line? If not, why weren’t you doing A/B testing instead? When you phrase it like that, it always scares the heck out of me but it’s kind of true. [Editor’s note: I often get very handwavy with that phrase “bottom line”: SaaS math does not work out such that 50% growth in rate of new account signups results in 50% to the bottom line. Work with me here — I’m from the land of one-time purchases, where modeling the effects of an A/B test is simple without having to literally start using calculus.]

Keith: You do need the other stuff, you can’t just A/B test your way to a successful business, but at the same time if you have down time, if you have any amount of time, like we said one line of code, five minutes, it’s not hard to do. If you have that time, you should be doing it.

Patrick: This should be your routine practice. If you make a new feature and you’re wondering if users are actually going to respond to it or not, put the new feature in an A/B test. It’s as simple as putting an if block around it. [Editor’s note: I’m trying to sell you something, not describe engineering reality here. Yeah, it can get substantially more complicated than “Wrap that in an if block.” Buy what I’m selling — you’ll be happy you did.]

Keith: I’m sure a lot of people are thinking, “But then you have to hire a designer and they have to make a mock‑up.” Even though it takes one line of code, it’s a pain to think about all these things. I do graphic design as well, but I show all my stuff to my wife and my friends to get a different perspective. Even if I don’t agree with their comments, even if their comments are batshit crazy, I test it because the cost of testing is so low. [Editor’s note: I do not endorse testing batshit crazy ideas.]

If it fails, it failed for three days and then it’s off the site and we’re never going to see it again. Sometimes you get nice results. I had a very nicely designed welcome page. My wife looked at it and said, “It’s too busy. Why don’t you try having no background?” Tried no background. 40 percent lift.

Patrick: You often see in design advice, for example at Smashing Magazine. I love designers — Keith is a designer and Keith is my best friend — but on the medical science scale, the discipline of design is closer to leeches than it is to medicine. I don’t like this design, so let’s add more leeches. We should make design more rigorous, like medicine: we’re going to test a treatment against a placebo and then see if it doesn’t kill people. Less leeches, more penicillin.

There was an article recently on Smashing Magazine that said if your body copy is less than 16 points you’re losing money. That’s a great headline, isn’t it, because that is a prediction about the measurable nature of reality. So you should be able to test that. I actually did test that. For Bingo Card Creator, I changed the body copy sitewide to 14 points for half of the population and 16 points in the other half of the population. [Editor’s note: BCC has used 14px for several years.]

Sure enough, I got a null result. “Null result” means that after a week and 20,000 people or whatever saw both variations, there did not exist data to conclude that 16 percent was different than 14 percent along the axis I was measuring. Good to know, right? [Editor’s note: 49,000 participants, actually. It was a good week.]

Keith: I do want to follow that up a little, doing a lot of graphic design myself. A lot of it is gut instinct. There are a lot of rules to design, but when you say something like “anything less than 16 point font is unreadable,” that really has to do with each page. You can’t just take any page, make all the font 16, and you’re suddenly going to have increased conversions. [Editor’s note: Bah, designers.]

Smashing Magazine spinning the story in that fashion was essentially linkbait. That’s the whole reason they did that. For some sites it might get you 20‑30 percent. It’s worth testing and in Patrick’s case it didn’t work. It all has to do with the design, it has to do with how the site feels, and for the particular users. Some users may want a green button, some users might want a red button.

If your users are the ones who want the green button and you give them a red button, no matter how well it converts on another person’s page, it’s not going to convert well for yours. For any design for anything you should test it on your own users instead of following just what other people say.

Patrick: That brings up a funny anecdote about users and culture. One of the versions of my Bingo Card Creator website was designed by a lady in India. (Editor’s note: Gursimran Kaur, whose name I avoided saying because I am unsure of the pronunciation, having never verbally spoken to her.) I asked her to design a pair of buttons for me, to represent downloading and creating cards. She thought that the action associated with creation was getting something from the website. Think of your hand going out, grabbing something, and taking it back to you.

So her button looked like a palm with splayed fingers oriented upwards on a red background, which in America means “Stop!”:

I had to say, “Hey, in America, this gesture does not suggest ‘Come get this!’ It means ‘No, no, no! Before you click this button think carefully. Do you really want to download this software? It will give your Googles a virus.'” [Editor’s note: I am poking light fun of my composite customer, who is not very technical, and as a result might use “the Googles” to mean, variously, the Internet, the web browser, or the entire experience of using a computer.]

We settled on a design of the download button that did not give their Googles a virus. It probably worked better.

Keith: You’ve made many buttons since then, of course. You’re very big into the color contrast. You want big, flashy buttons that say download this now.

Patrick: People make fun of me. I’ve been saying this stuff about A/B testing and whatnot for years. I make buttons bigger and it almost always works better. One of the English as a second language folks in one of my forums was talking one day and he’s like, “I know Patrick loves his big, orange, pancake buttons.” Big, orange, pancake button is my keyword for this now because big, orange, pancake buttons really effing work. Go ahead.

Keith: Except for these ones you tried last time. You had put these ones in and we were working together and he just turns to me and says, “I have these huge, new buttons and I really like them, but they’re just not converting well.” I look at them, they were really the ugliest things I’ve ever seen. They completely did not fit with the site at all. They were just offenses against God, honestly. [laughs]

Patrick: Right. I’ve been trying to get Keith to be my cofounder for the last couple of years. We’ll see if that happens.

Keith: We’ll see if that happens.

Patrick: One of the reasons I have been trying to recruit Keith for this kind of thing is because there’s this, I don’t know. Maybe it’s a skill, maybe it is an aptitude, maybe it is something your born with, but it is called taste. Whatever day God handed out the taste I was studying stats for D&D characters or something and totally missed it.

Keith: For action buttons for Patrick it’s generally bigger, oranger, more pancake‑y. It’s pretty much the order it goes in.

Patrick: With a little bit of rounding on the side.

Keith: You love the rounding.

Patrick: Good pancakes should be rounded and huge. Huge, rounded pancakes.

Keith: I think your Bingo Card Creator is just going to have a giant orange circle on it that says “Buy now.” You should split test that for April Fool’s Day.

Patrick: People wanted me to test that for a while. I was about to put an 800 by 600 button on my landing pages, but that would violate the Google AdWords content policies, which is problematic because most of the traffic to the landing pages comes from AdWords.

Speaking of which, interesting result from Fog Creek. Fog Creek decided to replace their FogBugz home page. It’s text‑heavy and tries to sell software to enterprise users. They replaced it with their kiwi logo and text similar to “FogBugz: The World’s Best Bug Tracking Software. Start Now.” No text. No screenshots. No philosophy. Just “Kiwi. Start now!”

Conversions went way up. At the same time, they fell off the Internet in terms of SEO. SEO and A/B testing exist to help the business. The business does not exist to help them. Despite the fact that that A/B test was successful, we couldn’t justify burning their Internet brand to continue it, the result was amusing.

Keith: Right. Actually, one thing you got from a similar test from Fog Creek is that people love to watch Joel talk.

Patrick: People love to watch Joel talk.

Keith: I love to listen to Joel talk. I actually listen to the StackExchange podcast just to hear Joel talk.

Patrick: This is why we’re doing a podcast right now, by the way, because Keith was so inspired by listening to the StackExchange podcast.

I don’t want to give the impression that all Fog Creek’s optimizations are my doing, by the way. I helped Fog Creek a few times with regards to their marketing, A/B testing and whatnot, but there are people in the company that are doing it pretty much every day. [Editor’s note: Fog Creek folks are ridiculously smart and they’re a wonderful company to work for. Does being their data-driven marketing guy interest you? Get in touch with them or get in touch with me — they’re hiring.]

One page frequently tested is the front page for FogBugz. For example, a page with a flat photo versus a design with a short three‑minute feature video versus a page with Joel Spolsky talking for an hour. The video is indirectly a sales pitch for FogBugz, but it’s mostly a pitch of how we should do software development better.

People watch that video for the entire hour. This just blows my mind. They’ve shown me a graph of what the level of attention is at various points in the interview. If you can imagine the graph for a Justin Bieber song on YouTube where everybody is listening at the first second and then X percent listen through the entire song, it’s that graph… but stretched out to an hour.

Granted, there’s probably not too many 14‑year‑old girls in the market for bug tracking software. A very different audience wants to watch Joel Spolsky talk for an hour about FogBugz. After they watch him for an hour, they are effing sold. Where is that button? They want it now.

Keith: Actually, that is an interesting trend. Joel talking for an hour is definitely above and beyond what I think most other companies can do. Video has always been the anathema of landing pages. You never put video on your landing page and stuff. Video now on landing pages is converting so much better than just text and I think it’s really going back to people don’t like to read.

Patrick: Right. People do not read on the Internet. If you take one thing from this podcast, people do not read on this Internet. [Editor’s note: It’s a pity that of the tens of thousands of people who see this post, only about five will actually read this comment. You’ll know who they are because they’ll race to mention it.]

Keith: They will click on a play button and listen to a 10 second clip over reading a paragraph.

Patrick: Yeah. It’s insane. This is one of those things where engineers have a totally different grasp of how the world works because most of us were precocious readers. We devour 600‑page Lord of the Ring books with no problem. That is severely anomalous behavior among the population at large.

If you install Crazy Egg, Crazy Egg will show you what percentage of people actually made it to a particular portion of a blog post or whatnot. The world, in general, is TL;DR after four words. It’s crazy. That’s why headers matter so much, by the way, because if they’re only going to read one sentence, make that sentence count.

Keith: Crazy Egg, if you use their scroll map, you will have so much wonderful information on your pages, especially if you have any page that requires scrolling for more than maybe three clicks.

Patrick: We just got done saying people don’t read on the Internet, but man, long copy. Long copy is those lovely pages that have hundreds and hundreds of paragraphs of talking you to death about the product. They just beat you into submission and then give you the buy button and then you actually buy. Do people actually buy from these, Keith?

Keith: One of my clients has very, very large long, long, long sales pages. I think it’s 68 pages printed. I looked at them and I was like, “There is no way people read these.” While 100 percent do not read the entire thing, 40 percent read the entire thing. 40 percent.

Patrick: That just blows my mind.

Keith: It absolutely blows my mind. The interesting thing now is that the sales button is not at the end of the page, it’s somewhere in the middle, and yet people read, go to the sales button, actually continue reading, and come back to the sales button in order to click it. That’s just amazing.

That’s 40 percent. 60 percent either don’t read it at all or just skim around. It’s really cool because you can see exactly where on the page people will stop, even for a slight amount of time. There’s this picture of a kind of cute girl with a blue Mohawk on. I hope I’m not giving out too much but it’s not a public page so I think it’s OK. 60 percent of people stop at that picture. It’s 40 percent, 40 percent, 40 percent and then blue Mohawk 60 percent. The area is just bright yellow on the heatmap. Everyone loves looking at this person.